Axon Growth: How to survive a nerve-wracking journey

Although many nerve fibres travel considerable distances as they develop, the motor axons that carry signals from the central nervous system to various muscles throughout the body must complete the neuronal equivalent of the Oregon Trail. Remarkably, these motor axons usually reach their targets and understanding how this happens has motivated generations of developmental neurobiologists.

The discovery of axon guidance molecules in the 1990s represented a major breakthrough in our efforts to understand how axons manoeuvre through the body to reach their final targets (Evans and Bashaw, 2010). Just as landmarks helped the early pioneers navigate their way along the Oregon trail to the western frontier of the US, guidance molecules provide axons with directions to their destination. Unfortunately, as with the pioneers, the survival of the neurons often depends on their axons making it to their final destination.

It has been hypothesized that intermediate targets might also provide such support en route, which has the effect of eliminating axons that stray off the trail early on (Wang and Tessier-Lavigne, 1999). However, in vivo evidence for this model has remained scarce. Now, in eLife, Zhong Hua, Philip Smallwood and Jeremy Nathans of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine present new evidence linking the arrival of motor axons at intermediate targets with neuronal survival (Hua et al., 2013).

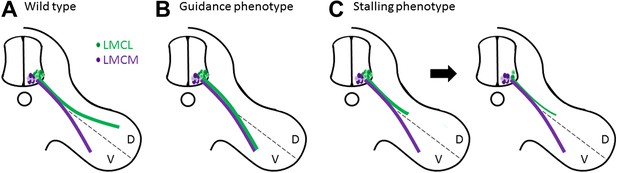

Muscles in the limbs receive input from neurons in the lateral motor column of the spinal cord. These neurons are further divided into lateral and medial groups, and although the axons projecting from these neurons leave the spinal cord together, their paths diverge within the limb to target dorsal and ventral muscles respectively (Figure 1A). Axons at this branching point must decide which region of the limb to enter, and then continue growing to reach all the muscles that control the movement of that limb. So how do the axons decide which road to take? The answer lies in the combinations of axon guidance signals provided by the developing limb, which give specific directions about where each axon should and should not grow (Bonanomi and Pfaff, 2010). In the absence of these signals, a dorsal axon might accidentally travel to the ventral muscles, or vice versa, resulting in what is called a guidance phenotype (Figure 1B; Helmbacher et al., 2000; Huber et al., 2005; Luria et al., 2008).

Motor axons usually reach their target, but sometimes they lose their way or stop growing and die.

(A) Two groups of neurons in the lateral motor column of the spinal cord target the developing limb. Although they leave the spinal cord together, their paths later diverge, with the neurons in the lateral group (green) innervating the dorsal (D) musculature and the neurons in the medial group (purple) innervating the ventral (V) musculature. Guidance molecules ensure that both sets of neurons reach the correct target. (B) In the absence of certain guidance molecules, one set of neurons might arrive at the wrong target. This defect is known as a guidance phenotype. (C) Hua et al. have discovered a pure stalling phenotype in which motor axons belonging to neurons in the lateral group set out on the correct path but stop growing, which results in the death of these neurons in the spinal cord.

When an axon encounters a guidance signal, it must choose to continue growing straight ahead, make a turn, or perhaps stop altogether. The decision is made within a specialized structure at the tip of the growing axon called the growth cone. How the growth cone actually responds to axon guidance signals remains poorly understood, but recent research into planar polarity proteins has unexpectedly uncovered a possible mechanism.

Planar polarity proteins help ensure that cells are properly aligned with their surrounding tissue (Wang and Nathans, 2007). As would be expected, the absence of planar polarity proteins impairs the formation of tissues that rely on cell alignment, such as hairs on the surface of our skin. However, the absence of Frizzled3 (Fz3)—a planar polarity protein that acts as a receptor in the well-known Wnt signalling pathway—also leads to serious defects in the central nervous system, notably a complete absence of many nerve tracts (Wang et al., 2002). These phenotypes seem to be caused by changes in the ability of growth cones to turn towards Wnt signals (Lyuksyutova et al., 2003; Shafer et al., 2011), confirming that planar polarity proteins ‘give directions’ to the axons, just like axon guidance molecules do.

In the case of motor neurons, Hua et al. find an unusual type of defect in Fz3 mutant mice. Through a detailed analysis of innervation patterns in the limbs, they show that the absence of Fz3 causes axons that should travel to the dorsal muscles to instead stall at the branch point (Figure 1C). Thus, these axons follow the right path but stop growing, likely because their growth cones cannot figure out which way to go. This stalling phenotype is fundamentally different from previously described guidance phenotypes, where the axons do eventually reach a target, albeit the wrong one.

Moreover, the stalling defect has a surprising consequence. When an axon fails to reach its final destination, the neuron in the lateral motor column to which it belongs actually dies. However, these neurons die two days earlier than expected. This suggests that they die because they do not receive support from an intermediate target: in other words, the axons never make it to the gas station to re-fuel.

Though axon stalling has been observed in other mouse mutants, this is a rare example where pure stalling is tied to cell death, providing important in vivo evidence that axons receive intermediate survival cues during their journey. Intriguingly, other cranial nerves also stall in Fz3 mutants, yet only a subset show an increase in cell death, suggesting that not all nerves require intermediate support. Are certain motor axons predisposed to require such support? Or do the unaffected motor axons rely on other members of the Frizzled family for their survival? What are the survival signals themselves, and do the same proteins also help axons choose their route?

It will also be important to determine how the failure of motor axons to extend fully into the limb fits with Fz3’s known role in guidance: are the nerves stalled because they don’t know which way to turn, or could this be an effect on the ability of the axon to grow at all? Understanding how all these pathways coalesce to produce a stereotyped trail of axon growth is proving to be an exciting path of research—thankfully, it does not involve the same perils.

References

-

Motor axon pathfindingCold Spring Harbor Perspectives on Biology 2:a001735.https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a001735

-

Axon guidance at the midline: of mice and fliesCurrent Opinion In Neurobiology 20:79–85.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2009.12.006

-

Targeting of the EphA4 tyrosine kinase receptor affects dorsal/ventral pathfinding of limb motor axonsDevelopment 127:3313–3324.

-

Frizzled-3 is required for the development of major fiber tracts in the rostral CNSJournal of Neuroscience 22:8563–8573.

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: December 17, 2013 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2013, Yung and Goodrich

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 569

- views

-

- 32

- downloads

-

- 0

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Neuroscience

Combining information from multiple senses is essential to object recognition, core to the ability to learn concepts, make new inferences, and generalize across distinct entities. Yet how the mind combines sensory input into coherent crossmodal representations - the crossmodal binding problem - remains poorly understood. Here, we applied multi-echo fMRI across a four-day paradigm, in which participants learned 3-dimensional crossmodal representations created from well-characterized unimodal visual shape and sound features. Our novel paradigm decoupled the learned crossmodal object representations from their baseline unimodal shapes and sounds, thus allowing us to track the emergence of crossmodal object representations as they were learned by healthy adults. Critically, we found that two anterior temporal lobe structures - temporal pole and perirhinal cortex - differentiated learned from non-learned crossmodal objects, even when controlling for the unimodal features that composed those objects. These results provide evidence for integrated crossmodal object representations in the anterior temporal lobes that were different from the representations for the unimodal features. Furthermore, we found that perirhinal cortex representations were by default biased towards visual shape, but this initial visual bias was attenuated by crossmodal learning. Thus, crossmodal learning transformed perirhinal representations such that they were no longer predominantly grounded in the visual modality, which may be a mechanism by which object concepts gain their abstraction.

-

- Genetics and Genomics

- Neuroscience

Genome-wide association studies have revealed >270 loci associated with schizophrenia risk, yet these genetic factors do not seem to be sufficient to fully explain the molecular determinants behind this psychiatric condition. Epigenetic marks such as post-translational histone modifications remain largely plastic during development and adulthood, allowing a dynamic impact of environmental factors, including antipsychotic medications, on access to genes and regulatory elements. However, few studies so far have profiled cell-specific genome-wide histone modifications in postmortem brain samples from schizophrenia subjects, or the effect of antipsychotic treatment on such epigenetic marks. Here, we conducted ChIP-seq analyses focusing on histone marks indicative of active enhancers (H3K27ac) and active promoters (H3K4me3), alongside RNA-seq, using frontal cortex samples from antipsychotic-free (AF) and antipsychotic-treated (AT) individuals with schizophrenia, as well as individually matched controls (n=58). Schizophrenia subjects exhibited thousands of neuronal and non-neuronal epigenetic differences at regions that included several susceptibility genetic loci, such as NRG1, DISC1, and DRD3. By analyzing the AF and AT cohorts separately, we identified schizophrenia-associated alterations in specific transcription factors, their regulatees, and epigenomic and transcriptomic features that were reversed by antipsychotic treatment; as well as those that represented a consequence of antipsychotic medication rather than a hallmark of schizophrenia in postmortem human brain samples. Notably, we also found that the effect of age on epigenomic landscapes was more pronounced in frontal cortex of AT-schizophrenics, as compared to AF-schizophrenics and controls. Together, these data provide important evidence of epigenetic alterations in the frontal cortex of individuals with schizophrenia, and remark for the first time on the impact of age and antipsychotic treatment on chromatin organization.