Neuroscience: Nerve endings reveal hidden diversity in the skin

Sensory neurons are the brain's portal to the external world. Four of the five traditional senses, the ‘special senses’ of vision, scent, hearing and taste, are conveyed by discrete sense organs that contain a few types of highly specialized signal transducing cells, such as rods and cones in the retina, or cochlear hair cells in the ear. However the sense of touch, which is conveyed by general somatic sensory neurons, is much less well defined. These neurons reside in discrete ganglia that lie peripheral to the brainstem and spinal cord, including the trigeminal ganglia that receive signals from the face and head, and the dorsal root ganglia that serve the trunk and limbs. Traditionally, somatic sensory neurons have been divided into three broad subtypes: nociceptors (for sensing pain), mechanoreceptors (for sensing touch), and proprioceptors (which sense body position). Nociceptors and mechanoreceptors terminate in the skin, whereas proprioceptors terminate in muscles and tendons.

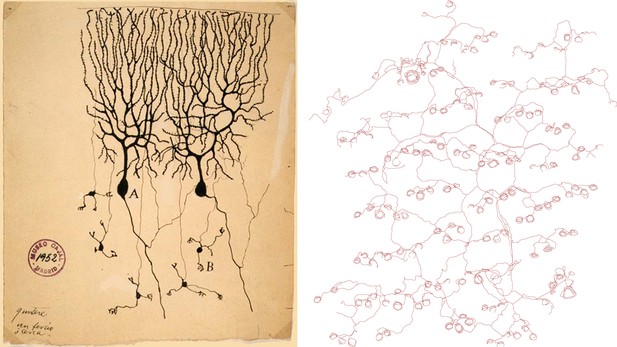

It has long been recognized that nerve endings in the skin display a diverse range of forms, but prior studies have generally used histological methods in tissue sections that do not reveal the complete morphology of each neuronal axon. Now, writing in eLife, Hao Wu, John Williams and Jeremy Nathans of Johns Hopkins University report the results of experiments that involve some very modern transgenic tricks, yet evoke the studies of neuronal morphology in the early 20th century—using methods introduced by Golgi and perfected by Ramón Y Cajal—that first revealed the complex architecture of single neurons (see Figure 1). The results of the Johns Hopkins experiment are largely descriptive in nature, and we might assume that the results reported are already buried somewhere in the literature, but they are not. Thus we are reminded that our knowledge of even well-studied experimental systems is still very fragmentary.

Drawings of neurons and nerve endings made more than a century apart. The drawing on the left was made by Santiago Ramón Y Cajal in 1899 and shows Purkinje cells in the cerebellum of a pigeon. The cells were stained with potassium dichromate and silver nitrate. The trace on the right shows nerve endings in the skin of a mouse. A combination of genetic and histochemical techniques were used to record the image from which the trace is taken (Wu et al., 2012).

IMAGE: INSTITUTO SANTIAGO RAMÓN Y CAJAL

This latest work was made possible by the Cre-Lox system—a widely-used approach in which a Cre recombinase enzyme is used to remove chromosomal DNA flanked by two genetically engineered loxP recognition sequences. Wu, Williams and Nathans used this method to excise a signal sequence blocking the expression of a histochemical marker gene which had been previously engineered into the chromosomal location of a transcription factor (Brn3a) that is important in the development of the sensory nervous system. A key feature of the experiments was the use of a form of the Cre enzyme that is translocated to the nucleus only in the presence of an estrogen-like drug, tamoxifen, so the probability that the marker gene is expressed should be related to tamoxifen concentration. By trial-and-error titration of the tamoxifen dose administered to pregnant mice bearing transgenic litters, it was possible to label a small number of discrete sensory neurons.

The Johns Hopkins researchers attempt to systematically categorize, for the first time, the complex axons of many individual sensory neurons with respect to their morphology, the number and density of their endings, and also their relationship to hair follicles, where most of the fibers terminate. They acknowledge that this must be a preliminary system, because only a subset of sensory neurons is sampled. One class of axon terminal may be consistent with fibers conveying itch sensation, but most of the endings conveying pain, pleasant and unpleasant temperatures, and chemical irritants are probably not revealed by the labeling method used. One particularly interesting class of labeled neuron possesses axons with C-shaped endings that only partly encircle hair follicles, and that terminate on a consistent side of the follicles arrayed across a large skin area. This structure may be especially suited to convey the direction of movement of tactile stimuli across the skin. Recently it has become possible to correlate some well-known markers of sensory subtypes with the terminal morphology and electrophysiological properties of mechanoreceptors (Li et al., 2011), and the function of most of the mechanoreceptors identified here await further physiological studies.

It will be interesting to see to what extent these diverse patterns of nerve endings are pre-ordained by gene regulatory programs during the developmental period when the axons are growing out from the sensory ganglia, and how much is adaptive. The overall gene regulatory cascade for the early specification of pain, touch and proprioceptive somatic sensory neurons is now fairly well understood (Liu and Ma, 2011). In mice lacking the transcription factors Islet1 and Brn3a (the gene locus used to target the reporter in this study), sensory neurons remain in a generic ‘ground state’ of differentiation and express few subtype specific markers (Dykes et al., 2011). Recent work has shown that the receptor tyrosine kinase cRet (Luo et al., 2009) and the transcription factor cMaf (Wende et al., 2012) are required for the development of some classes of mechanoreceptors. However, none of these developmental mechanisms comes close to offering an explanation for the diversity of sensory arbors observed by Wu, Williams and Nathans. If a large part of the diversity observed in the present study is genetically determined, then much the regulatory program of sensory differentiation is yet unknown.

A related question is whether the pattern of arborization will be similar in regions of skin with very different sensory properties. It is well known that the size of touch receptive fields differs widely between areas that are sparsely innervated, such as the trunk skin studied by the Johns Hopkins group, and those that are densely innervated, such as the face and fingertips. In areas with finer resolution of tactile stimuli, such as the distal limbs and face, the arbors should have smaller territories and/or have more densely packed endings. Also, since the majority of neurons described here innervate hair follicles, the glabrous skin of the hands and feet must necessarily have differently structured endings and arbors.

It is remarkable that in the brachial and lumbar regions, the receptive field of a single dorsal root ganglion may encompass a continuous area of skin from the mid-back to the tips of the digits (Takahashi et al., 2003). A single dorsal root ganglion must therefore contain at least three fundamental classes of sensory neuron, with remarkable morphological and functional diversity expressed in each class. The Johns Hopkins study is only a ‘first pass’ at a systematic description of this diversity, so it is possible that a truly remarkable range of neuronal form and function will ultimately be found within a single sensory ganglion that contains just a few thousand neurons.

References

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: December 18, 2012 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2012, Turner

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,425

- Page views

-

- 52

- Downloads

-

- 0

- Citations

Article citation count generated by polling the highest count across the following sources: Crossref, PubMed Central, Scopus.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Developmental Biology

We previously showed that SerpinE2 and the serine protease HtrA1 modulate fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling in germ layer specification and head-to-tail development of Xenopus embryos. Here, we present an extracellular proteolytic mechanism involving this serpin-protease system in the developing neural crest (NC). Knockdown of SerpinE2 by injected antisense morpholino oligonucleotides did not affect the specification of NC progenitors but instead inhibited the migration of NC cells, causing defects in dorsal fin, melanocyte, and craniofacial cartilage formation. Similarly, overexpression of the HtrA1 protease impaired NC cell migration and the formation of NC-derived structures. The phenotype of SerpinE2 knockdown was overcome by concomitant downregulation of HtrA1, indicating that SerpinE2 stimulates NC migration by inhibiting endogenous HtrA1 activity. SerpinE2 binds to HtrA1, and the HtrA1 protease triggers degradation of the cell surface proteoglycan Syndecan-4 (Sdc4). Microinjection of Sdc4 mRNA partially rescued NC migration defects induced by both HtrA1 upregulation and SerpinE2 downregulation. These epistatic experiments suggest a proteolytic pathway by a double inhibition mechanism:

SerpinE2 ┤HtrA1 protease ┤Syndecan-4 → NC cell migration.

-

- Developmental Biology

- Neuroscience

Human fetal development has been associated with brain health at later stages. It is unknown whether growth in utero, as indexed by birth weight (BW), relates consistently to lifespan brain characteristics and changes, and to what extent these influences are of a genetic or environmental nature. Here we show remarkably stable and lifelong positive associations between BW and cortical surface area and volume across and within developmental, aging and lifespan longitudinal samples (N = 5794, 4–82 y of age, w/386 monozygotic twins, followed for up to 8.3 y w/12,088 brain MRIs). In contrast, no consistent effect of BW on brain changes was observed. Partly environmental effects were indicated by analysis of twin BW discordance. In conclusion, the influence of prenatal growth on cortical topography is stable and reliable through the lifespan. This early-life factor appears to influence the brain by association of brain reserve, rather than brain maintenance. Thus, fetal influences appear omnipresent in the spacetime of the human brain throughout the human lifespan. Optimizing fetal growth may increase brain reserve for life, also in aging.