Visual Behavior: The eyes have it

Like us, flies depend on their sense of sight. When a fly perceives an approaching object, such as a fly swatter, it repositions itself and executes an escape strategy in less time than the blink of an eye (Card and Dickinson, 2008). Flies produce an impressive repertoire of visual behaviors, including escape, with a brain that contains a relatively small number of neurons. Drosophila melanogaster, the fruit fly, has become an enormously useful model for studying visual behavior, yet the neural mechanisms for transforming object signals (such as an approaching swatter) into motor actions (escape) remain poorly understood.

The Drosophila retina is composed of roughly 700 hexagonal facets, each viewing a small portion of the visual field, and signals from the photoreceptors within each facet are processed by four optic lobes in the brain. The processing in these optic lobes happens in a retinotopic fashion: in other words, signals from neighboring facets are passed through the optic lobes by neighboring columns of neurons. The signals are first processed by an optic lobe called the lamina, followed by the medulla, and then the lobula and the lobula plate (Figure 1). The last two lobes collate retinotopic information from all the inputs and project axons that carry filtered signals to structures elsewhere in the brain.

Transforming visual signals into motor actions.

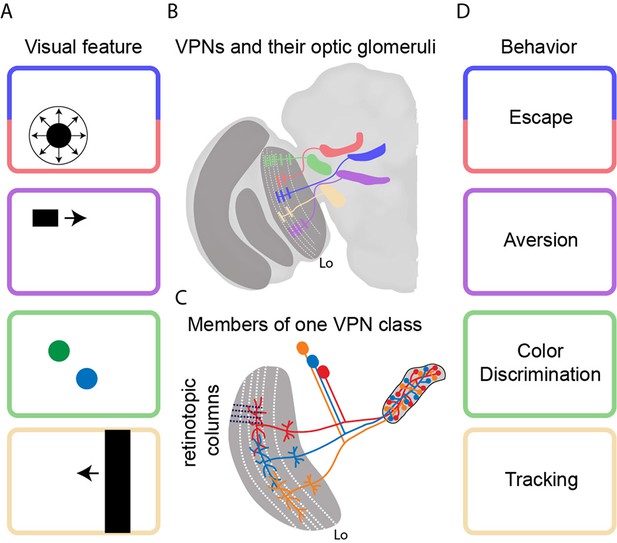

(A) Visual features that are important to the fly include looming (top), small moving objects, colors, and vertical edges. (B) Wu et al. identified 22 different classes of visual projection neurons (VPNs) in the lobula (Lo), with all the neurons in a given class projecting to a specific glomerulus in the brain. Five examples are shown schematically. Wu et al. also observed that the neurons have dendritic innervations within anatomically distinct layers of the lobula (indicated by white dashed lines). (C) Neighboring columns of neurons in the lobula (indicated by black dashed lines) sample neighboring regions of space. The neurons in a given VPN class have overlapping dendritic fields, which corresponds to overlaps in the sampling of visual space. The axon terminals, on the other hand, completely innervate the glomerulus for that VPN class. (D) It is thought that each VPN class responds to a visual feature (panel A) and contributes to a particular form of behavior (panel D).

Lobula plate neurons have been studied for 60 years and it is known that they compute patterns of visual motion across the eye to guide navigation tasks (Borst, 2014). However, much less is known about the lobula, even though it contains four times as many neurons (Strausfeld, 1976). Now, in eLife, Aljoscha Nern, Gerald Rubin and colleagues at the Janelia Research Campus – including Ming Wu and Nern as joint first authors – report the results of a series of anatomical and behavioral experiments to understand the architecture and functions of these neurons (Wu et al., 2016). In particular they identify 22 different classes of visual projection neurons (VPN) in the lobula, and show that specific classes of neurons elicit specific visual behaviors, such as escape.

The power of Drosophila genetics is deployed in full force here. Wu et al. first screened large collections of genetically modified flies to find lines in which it is possible to fluorescently label all the retinotopic neurons of a given VPN class that project from the lobula to the center of the brain. Then they stochastically labeled a few individual neurons in each of the 22 VPN classes with different fluorescent colors. This systematic approach allowed them to take high-resolution pictures of input dendrites and output axon terminals, and to demonstrate that each VPN class had a characteristic number of cells, dendritic span, and axon output location (Figure 1B). Whereas the input dendrites in each class were organized in a retinotopic fashion, the axon terminals were fully intermingled to form an optic glomerulus. Strikingly, it would appear that the spatial information contained in the inputs is thrown away because it is not contained in the outputs (Figure 1C).

Next, Wu et. al. investigated the behavioral role of each VPN class by testing whether the use of light to activate the neurons in a particular class provoked any observable behavioral reactions. Activation of two classes (called LC6 and LC16) resulted in significant jumping and backward walking, which are hallmarks of visual escape behavior. In further tests strong calcium currents were detected in both classes when the flies were presented with a looming stimulus (like an approaching fly swatter). It would appear that LC6 and LC16 neurons transform looming visual information into the motor control of a rapid escape behavior (also see von Reyn et al., 2014).

In addition to shedding new light on lobula projection neurons, the work of Wu et al. also raises exciting new questions. 1) What is the functional benefit of losing the retinotopic information that was contained in the input to the lobula? 2) Individual members of a given class have overlapping dendritic fields, which means that a given region of visual space is covered more than once: what is the benefit to this oversampling? 3) As Wu et al. demonstrate, a single type of behavior can be initiated by more than one class of neurons. This means that activating a given class may be sufficient to provoke a specific behavior, but silencing the same class does not necessarily quell that behavior. What gives rise to the apparent redundancy within the brain? 4) We recently performed a complimentary comprehensive physiological characterization of one these VPN classes: this study revealed complex spatial inhibitory interactions, indicating that only a fraction of the neurons in this class are activated by the salient visual stimulus (Keleş and Frye, 2017). Therefore, as Wu et al. note, the use of optogenetic techniques to simultaneously activate the whole population of neurons does not mimic what happens naturally. How does the output sent to the glomerulus reflect the spatial dynamics of the inputs?

Based on what we currently know about the functional properties of lobula visual projection neurons (Keleş and Frye, 2017; Mu et al., 2012), activity within a given optic glomerulus seems to correspond to the presence of a visual feature rather than its direction of movement or spatial location. In flies and mammals, the spatial pattern of olfactory glomeruli can signal the identity and intensity of an odorant (Wang et al., 2003). Perhaps something similar is happening here, with the pattern of activation across different optic glomeruli signaling particular features of visual objects rather than their motion or location. The approaches developed by Wu et al. are likely to prove very useful for exploring this hypothesis and for studying how visual representations are transformed into behavioral commands more generally.

References

-

Fly visual course control: behaviour, algorithms and circuitsNature Reviews Neuroscience 15:590–599.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3799

-

Visually mediated motor planning in the escape response of DrosophilaCurrent Biology 18:1300–1307.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.094

-

A spike-timing mechanism for action selectionNature Neuroscience 17:962–970.https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3741

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: February 6, 2017 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2017, Keleş et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,874

- views

-

- 200

- downloads

-

- 5

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Neuroscience

Improving our understanding of autism, ADHD, dyslexia and other neurodevelopmental conditions requires collaborations between genetics, psychiatry, the social sciences and other fields of research.

-

- Genetics and Genomics

- Neuroscience

Genome-wide association studies have revealed >270 loci associated with schizophrenia risk, yet these genetic factors do not seem to be sufficient to fully explain the molecular determinants behind this psychiatric condition. Epigenetic marks such as post-translational histone modifications remain largely plastic during development and adulthood, allowing a dynamic impact of environmental factors, including antipsychotic medications, on access to genes and regulatory elements. However, few studies so far have profiled cell-specific genome-wide histone modifications in postmortem brain samples from schizophrenia subjects, or the effect of antipsychotic treatment on such epigenetic marks. Here, we conducted ChIP-seq analyses focusing on histone marks indicative of active enhancers (H3K27ac) and active promoters (H3K4me3), alongside RNA-seq, using frontal cortex samples from antipsychotic-free (AF) and antipsychotic-treated (AT) individuals with schizophrenia, as well as individually matched controls (n=58). Schizophrenia subjects exhibited thousands of neuronal and non-neuronal epigenetic differences at regions that included several susceptibility genetic loci, such as NRG1, DISC1, and DRD3. By analyzing the AF and AT cohorts separately, we identified schizophrenia-associated alterations in specific transcription factors, their regulatees, and epigenomic and transcriptomic features that were reversed by antipsychotic treatment; as well as those that represented a consequence of antipsychotic medication rather than a hallmark of schizophrenia in postmortem human brain samples. Notably, we also found that the effect of age on epigenomic landscapes was more pronounced in frontal cortex of AT-schizophrenics, as compared to AF-schizophrenics and controls. Together, these data provide important evidence of epigenetic alterations in the frontal cortex of individuals with schizophrenia, and remark for the first time on the impact of age and antipsychotic treatment on chromatin organization.