Cancer Therapeutics: Partial loss of genes might open therapeutic window

Copy number loss – which involves part of a chromosome being deleted during DNA replication – is a common occurrence in cancer. While the loss of tumor suppressor genes during copy number loss can promote the formation of tumors, the loss of other genes in these same regions was not thought to be relevant to cancer. In 2012, however, Rameen Beroukhim, William Hahn and co-workers analyzed a panel of 86 cancer cell lines to search for genes with a particular property – the deletion of one copy of the gene results in cells that are less able to withstand further down-regulation of gene expression than cells with two copies of the gene (Nijhawan et al., 2012). A total of 56 CYCLOPS genes were identified, many of which were found to encode proteins that are essential for cell survival. In general, genes that encode essential proteins are not pursued as drug targets, but the vulnerability of cancer cells that have lost one copy of an essential gene might create a therapeutic window.

Now, in eLife, Beroukhim, Robin Reed and co-workers – including Brenton Paolella and William Gibson as joint first authors – report how an analysis of 179 cell lines has allowed them to identify a total of 124 CYCLOPS candidate genes (Paolella et al., 2017). Many of these genes encode proteins that are part of a complex molecular machine called the spliceosome: in particular, the gene SF3B1 encodes a protein that is the largest subunit in the SF3b complex which, in turn is part of a small nuclear ribonucleoprotein called the U2 snRNP complex. The spliceosome contains a total of five such ribonucleoproteins.

Although mutations in SF3B1 have been observed in patients with a wide range of cancers, the loss of one copy of the gene is far more common than mutation. Across some 10,570 cases in the Cancer Genome Atlas, Paolella et al. – who are based at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, Brigham and Women's Hospital and the Broad Institute – found that partial deletion of SF3B1 occurs most frequently in chromophobe kidney cancer, urothelial bladder cancer, and breast cancer. The fact that none of the patients in the atlas had lost both copies of SF3B1 is consistent with it being an essential gene. Previous work on SF3B1 has shown that mutations and partial loss have distinct effects on splicing (Alsafadi et al., 2016).

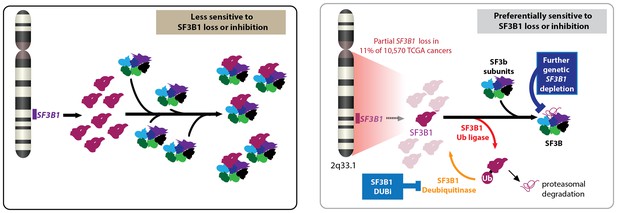

Paolella et al. then performed a series of biochemical studies to explore how the partial loss of SF3B1 effected the abundance of the SF3b and U2 snRNP complexes in cells that had lost a copy of the gene and cells that were copy neutral (that is, had not lost or gained a copy of the gene). These studies revealed that cells that had lost a copy of the gene were highly sensitive to further down-regulation of the gene, because they did not have sufficient levels of the SF3b complex, whereas the copy neutral cells were more tolerant to down-regulation of the gene (Figure 1).

Partial loss of SF3B1 and cancer.

Left: The gene SF3B1 encodes a protein (maroon) that is part of the SF3b complex (multiple colors), which is part of the spliceosome (not shown). Right: A significant number of cancer cells contain just one copy of SF3B1, rather than two, which leads to a reduced abundance of the SF3b complex in cells. Such cells are sensitive to further loss of SF3B1 through genetic down-regulation (top) or ubiquitination by a ligase (bottom). Cancer cells employ deubiquitinases to reverse the effects of ubiquitination, so drugs that inhibit these deubiquitinases could be used to treat some cancers. CYCLOPS: copy-number alterations yielding cancer liabilities owing to partial loss; DUBi: deubiquitinase inhibitor.

In the past decade it has been shown that compounds that inhibit SF3B1 have potent anti-tumor activity (Kaida et al., 2007; Folco et al., 2011). These inhibitors appear to perturb U2 snRNP function without altering the level of the SF3B1 or U2 snRNP complexes. SF3B1 mutant cells are more sensitive to these inhibitors than their wild-type counterparts (Obeng et al., 2016). However, partial loss of SF3B1 does not appear to make cells more sensitive to these inhibitors.

In an effort to find a way to exploit the vulnerability of cells that had experienced a partial loss of SF3B1, Paolella et al. found that the regulatory protein ubiquitin had a central role in the function of the SF3B1 protein and in SF3B1-related cancer vulnerability (Figure 1). In particular, enzymes called ligases catalyzed the addition of ubiquitin to the SF3B1 protein, thus "tagging" it for degradation in the proteasome. However, other enzymes called deubiquitinases reversed this process, thus helping the cell to survive. Paolella et al. then showed that a drug called b-AP15, which was known to inhibit various deubiquitinases (D'Arcy et al., 2011), could inhibit the deubiquitinases in cancer cells that had experienced partial loss of SF3B1, and thus selectively kill these cells by reducing the amount of SF3B1 protein.

The next challenge is to identify the specific ubiquitin ligases and deubiquitinases for the SF3B1 protein, and to check for possible side effects of any drugs used to inhibit the relevant deubiquitinases.

Nonetheless, the work of Paolella et al. will, we hope, ultimately provide a number of new avenues for targeting the spliceosome in order to treat cancer.

References

-

Inhibition of proteasome deubiquitinating activity as a new Cancer therapyNature Medicine 17:1636–1640.https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.2536

-

Spliceostatin A targets SF3b and inhibits both splicing and nuclear retention of pre-mRNANature Chemical Biology 3:576–583.https://doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.2007.18

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: March 17, 2017 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2017, Liu et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,110

- views

-

- 197

- downloads

-

- 2

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Cancer Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

Relapse of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is highly aggressive and often treatment refractory. We analyzed previously published AML relapse cohorts and found that 40% of relapses occur without changes in driver mutations, suggesting that non-genetic mechanisms drive relapse in a large proportion of cases. We therefore characterized epigenetic patterns of AML relapse using 26 matched diagnosis-relapse samples with ATAC-seq. This analysis identified a relapse-specific chromatin accessibility signature for mutationally stable AML, suggesting that AML undergoes epigenetic evolution at relapse independent of mutational changes. Analysis of leukemia stem cell (LSC) chromatin changes at relapse indicated that this leukemic compartment underwent significantly less epigenetic evolution than non-LSCs, while epigenetic changes in non-LSCs reflected overall evolution of the bulk leukemia. Finally, we used single-cell ATAC-seq paired with mitochondrial sequencing (mtscATAC) to map clones from diagnosis into relapse along with their epigenetic features. We found that distinct mitochondrially-defined clones exhibit more similar chromatin accessibility at relapse relative to diagnosis, demonstrating convergent epigenetic evolution in relapsed AML. These results demonstrate that epigenetic evolution is a feature of relapsed AML and that convergent epigenetic evolution can occur following treatment with induction chemotherapy.

-

- Cancer Biology

- Cell Biology

Rapid recovery of proteasome activity may contribute to intrinsic and acquired resistance to FDA-approved proteasome inhibitors. Previous studies have demonstrated that the expression of proteasome genes in cells treated with sub-lethal concentrations of proteasome inhibitors is upregulated by the transcription factor Nrf1 (NFE2L1), which is activated by a DDI2 protease. Here, we demonstrate that the recovery of proteasome activity is DDI2-independent and occurs before transcription of proteasomal genes is upregulated but requires protein translation. Thus, mammalian cells possess an additional DDI2 and transcription-independent pathway for the rapid recovery of proteasome activity after proteasome inhibition.