Evolutionary Developmental Biology: Sensing oxygen inside and out

For single-celled organisms like bacteria, every cell can detect changes in the level of oxygen in its environment and respond accordingly. Things, however, can be rather more complicated in multicellular organisms (Jonz et al., 2016). For example, animals must have a respiratory system to deliver enough oxygen to millions of cells to meet with their metabolic demands. An animal’s survival also depends on it monitoring oxygen levels both internally (for example, in its blood) and externally (in the environment). Multicellular organisms have oxygen sensors that consist largely of cells called neuroendocrine cells. When oxygen levels drop, these sensors release neurotransmitters, chemicals that excite nearby neurons to signal to a control center in the brain. The control center then triggers reflexes that increase the frequency of breathing.

These oxygen sensors have evolved at strategic places in the body. In land animals like mammals and birds (collectively referred to as amniotes), these sensors are found in two distinct locations: next to the carotid arteries, and in the airways of the lungs. The carotid arteries are the major blood vessels that deliver oxygenated blood to the head and neck, and the neuroendocrine cells are packed closely together to form a structure called the carotid body located where these arteries branch. In the airways of the lungs, the oxygen sensors are distributed as single cells or in small groups known as neuroendocrine bodies, present mostly at the branch-points. Primarily aquatic species, like fish and amphibians (collectively referred to as non-amniotes), have oxygen-sensing neuroendocrine cells in their gills to detect oxygen in the water. At least one fish, the jawless lamprey, also has oxygen-sensitive cells that are rich in neurotransmitters near its major blood vessels, reminiscent of the carotid body found in the land animals (Jonz et al., 2016).

The multiple similarities of neuroendocrine cells in these different structures have led to a long-lasting debate as to how they are related in terms of evolution, particularly whether the neuroendocrine cells in the carotid body and the lungs of land animals evolved from the neuroendocrine cells in the gills of their aquatic ancestors. Now, in eLife, Clare Baker at the University of Cambridge and colleagues – including Dorit Hockman as first author – address this controversy and report that these different oxygen sensors diverged long before animals transitioned onto land (Hockman et al., 2017).

Previous studies in mice and birds had already shown that lung neuroendocrine cells have a different embryonic origin than those found in the carotid body. Most animal embryos form three distinct layers during the early stages of development: endoderm, mesoderm and ectoderm. These layers later contribute to different parts of the body. The neuroendocrine cells in the lung develop from the endoderm, while those in the carotid body develop from the neural crest, which arises from the ectoderm (Pearse et al., 1973; Hoyt et al., 1990; Song et al., 2012; Kuo and Krasnow, 2015).

To decipher the evolutionary relationships between the oxygen sensors, Hockman et al. – who are based at institutions in Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, the US and the UK – set out to determine the origin of the gill neuroendocrine cells. To do this, they traced how neuroendocrine cells develop in the embryos of three non-amniotes: namely two species of fish (lamprey and zebrafish) and one species of frog (Xenopus). First, they engineered zebrafish so that all cells derived from the neural crest would fluoresce red. However, no red cells were seen in the gills, which indicated that gill neuroendocrine cells are not neural crest-derived. The finding that zebrafish mutants which lack neural crest cells still developed neuroendocrine cells in their gills further supported this conclusion. Importantly, Hockman et al. went on to confirm that the neuroendocrine cells in the zebrafish gills develop from endodermal cells, just like those in the lungs of mice. Similar results were seen with lamprey and Xenopus.

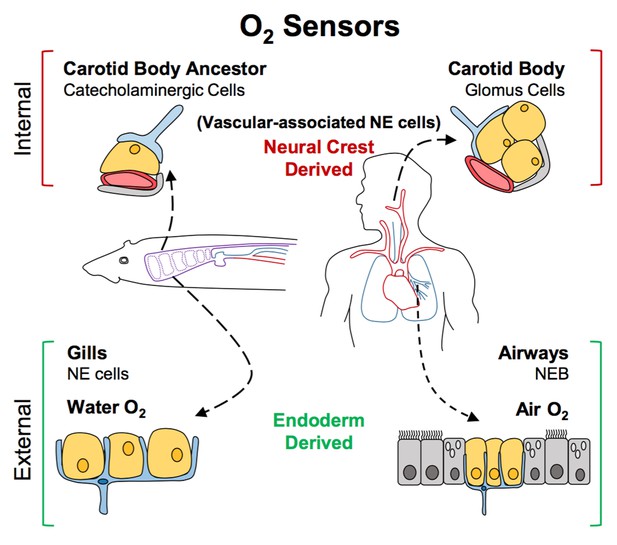

The finding that during development neuroendocrine cells in gills arise from the endoderm and not the neural crest effectively ruled out the possibility that they could have evolved from the same precursor cell as carotid body cells. Hockman et al. then identified neural crest-derived cells rich in neurotransmitters near major blood vessels in young lamprey and zebrafish. Specifically, these cells were found near large blood vessels of the fish’s pharyngeal arches, an association that closely resembles that seen in the carotid bodies of land animals. This led Hockman et al. to propose a new model for the evolution of oxygen sensors (Figure 1). According to this model, the carotid body seen in amniotes evolved from the grouping together of the neural crest-derived cells that were present near the pharyngeal arches of non-amniotes (which eventually develop into the gill arches). Later, these cells altered the neurotransmitters that they produced, and became wired into the nervous system. By contrast, the neuroendocrine cells in the gills and lungs continued to develop in situ from endodermal cells when animals transitioned from an aquatic to a terrestrial life.

A new model for the evolution of oxygen sensors.

Oxygen-sensitive neuroendocrine (NE) cells (yellow) associated with blood vessels (red) serve as sensors for internal oxygen levels (top). These include catecholaminergic cells in an ancestral structure in non-amniotes like fish (left), and the glomus cells in the carotid body of amniotes like humans (right). Other neuroendocrine cells act as sensors for external oxygen (bottom). These include cells in the gills of fish (left) and the airways of amniotes (right). Hockman et al. propose that the clusters of catecholaminergic cells near the blood vessels in non-amniotes evolved into the carotid bodies of amniotes. The neuroendocrine cells in these internal sensors are all derived from the neural crest. By contrast, the external oxygen sensors in gills and airways are derived from the endoderm in both non-amniotes and amniotes. Neurons are shown in blue; accessory cells are shown in gray. NEB: neuroendocrine body.

The challenge ahead is to elucidate the network of genes that led oxygen-sensing structures to diversify as animals evolved. Some of the signals needed for neuroendocrine cells to develop are already known (Borges et al., 1997; Ito et al., 2000; Kameda, 2005; Tsao et al., 2009; Branchfield et al., 2016). However, there is evidence that each type of sensor requires slightly different cues and produces a different combination of molecules (Dauger et al., 2003). Additional knowledge of these differences will help us to understand how these sensors acquired their specialized functions to fulfill new roles during evolution.

References

-

Basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors regulate the neuroendocrine differentiation of fetal mouse pulmonary epitheliumDevelopment 127:3913–3921.

-

Sensing and surviving hypoxia in vertebratesAnnals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1365:43–58.https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12780

-

Mash1 is required for glomus cell formation in the mouse carotid bodyDevelopmental Biology 283:128–139.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.04.004

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: May 19, 2017 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2017, Stupnikov et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,997

- views

-

- 282

- downloads

-

- 3

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Developmental Biology

- Evolutionary Biology

Despite rapid evolution across eutherian mammals, the X-linked MIR-506 family miRNAs are located in a region flanked by two highly conserved protein-coding genes (SLITRK2 and FMR1) on the X chromosome. Intriguingly, these miRNAs are predominantly expressed in the testis, suggesting a potential role in spermatogenesis and male fertility. Here, we report that the X-linked MIR-506 family miRNAs were derived from the MER91C DNA transposons. Selective inactivation of individual miRNAs or clusters caused no discernible defects, but simultaneous ablation of five clusters containing 19 members of the MIR-506 family led to reduced male fertility in mice. Despite normal sperm counts, motility, and morphology, the KO sperm were less competitive than wild-type sperm when subjected to a polyandrous mating scheme. Transcriptomic and bioinformatic analyses revealed that these X-linked MIR-506 family miRNAs, in addition to targeting a set of conserved genes, have more targets that are critical for spermatogenesis and embryonic development during evolution. Our data suggest that the MIR-506 family miRNAs function to enhance sperm competitiveness and reproductive fitness of the male by finetuning gene expression during spermatogenesis.

-

- Developmental Biology

We previously showed that SerpinE2 and the serine protease HtrA1 modulate fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling in germ layer specification and head-to-tail development of Xenopus embryos. Here, we present an extracellular proteolytic mechanism involving this serpin-protease system in the developing neural crest (NC). Knockdown of SerpinE2 by injected antisense morpholino oligonucleotides did not affect the specification of NC progenitors but instead inhibited the migration of NC cells, causing defects in dorsal fin, melanocyte, and craniofacial cartilage formation. Similarly, overexpression of the HtrA1 protease impaired NC cell migration and the formation of NC-derived structures. The phenotype of SerpinE2 knockdown was overcome by concomitant downregulation of HtrA1, indicating that SerpinE2 stimulates NC migration by inhibiting endogenous HtrA1 activity. SerpinE2 binds to HtrA1, and the HtrA1 protease triggers degradation of the cell surface proteoglycan Syndecan-4 (Sdc4). Microinjection of Sdc4 mRNA partially rescued NC migration defects induced by both HtrA1 upregulation and SerpinE2 downregulation. These epistatic experiments suggest a proteolytic pathway by a double inhibition mechanism:

SerpinE2 ┤HtrA1 protease ┤Syndecan-4 → NC cell migration.