Apoptosis: Keeping inflammation at bay

The cells in our bodies are genetically programmed to undergo a natural process of self-destruction called apoptosis, after which the dying cell is removed by cells that have the ability to engulf them (‘phagocytes’). The membrane of the dying cell is still intact as it is engulfed by the phagocyte, so its contents do not come into contact with other nearby cells. Apoptosis does not trigger inflammation, whereas another form of cell death called necrosis—in which the cell membrane is ruptured—is often associated with inflammation (Kerr et al., 1972).

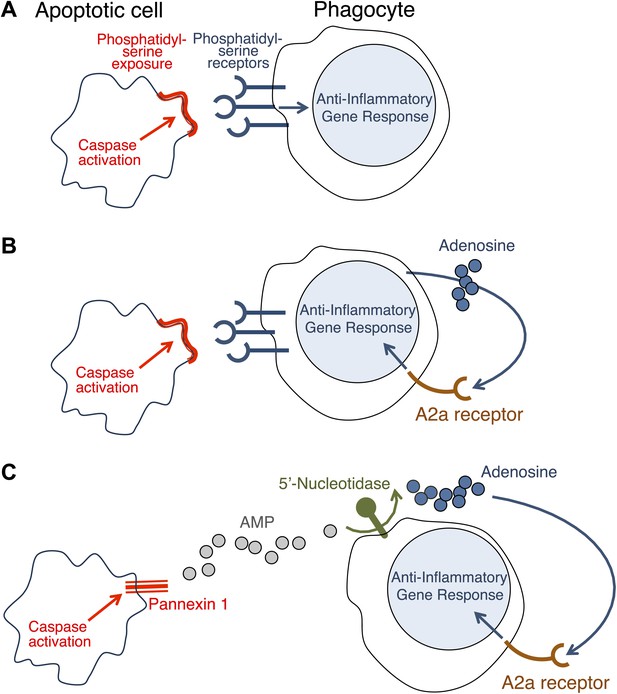

Necrosis causes inflammation because some components of the dying cell that are capable of triggering inflammation come into contact with healthy cells nearby (Rock and Kono, 2008). At first it was assumed that the only reason why apoptosis did not cause inflammation was that all the contents of the dying cell remained inside the membrane and the phagocyte. However, it was later discovered that apoptosis can actually block inflammation (Voll et al., 1997; Fadok et al., 1998). Initial observations suggested that this anti-inflammatory effect is triggered when the phagocytes are exposed to phosphatidylserine—a molecule on the surface of apoptotic cells that has a central role in phagocytosis (Huynh et al., 2002). It seemed, therefore, that these anti-inflammatory changes could be induced only in cells intimately associated with the dying cell (Figure 1A).

How do apoptotic cells trigger an anti-inflammatory response in phagocytes?

(A) Phosphatidylserine molecules on the surface of an apoptotic cell can bind to phosphatidylserine receptors on the surface of a phagocyte and previously it was suggested that this triggered an anti-inflammatory gene response. (B) It was also suggested that the direct apoptotic cell–phagocyte interaction shown in A also results in the release of adenosine by the phagocyte: this adenosine can bind to A2a receptors on the surface of the phagocyte and trigger an anti-inflammatory gene response. (C) Yamaguchi et al. found that the apoptotic cell releases a molecule called adenosine monophosphate (AMP) that is converted to adenosine by a 5′-nucleotidase on the surface of the phagocyte. The adenosine can then trigger an anti-inflammatory gene response by binding to A2a receptors. Enzymes called caspases play a central role in apoptosis in a variety of ways. The action of these caspases is required for the exposure of phosphatidylserine on the surface of the apoptotic cells (A and B); they also activate a channel protein called pannexin-1 to allow the release of AMP (C).

Now, in eLife, Shigekazu Nagata and co-workers at Kyoto University and the Osaka Bioscience Institute—including Hiroshi Yamaguchi as first author—report that apoptotic cells release a molecule called adenosine that can activate an anti-inflammatory gene response in phagocytes (Yamaguchi et al., 2014). They have also shown that adenosine activates this response by stimulating the A2a adenosine receptor in phagocytes.

Similar results have been reported before (Sitkovsky and Ohta, 2005; Köröskényi et al., 2011), but it had been thought that the adenosine was generated by the phagocytes as a consequence of their uptake of the apoptotic cells (Figure 1B). Yamaguchi et al. now show that the adenosine comes from the apoptotic cells themselves, with the phagocytes having only a secondary role in its production. The first step involves enzymes called caspases—which have a central role in apoptosis—cleaving a membrane channel protein called pannexin-1 in the dying cells, and thereby activating it. This results in the release of adenosine monophosphate (AMP) from the dying cells. A 5′-nucleotidase expressed by the phagocytes then removes a phosphate group from the AMP to yield adenosine. The adenosine then binds to the A2a receptor on the phagocytes to trigger an anti-inflammatory gene response (Figure 1C).

Adenosine is not the only soluble molecule released by apoptotic cells to perform a specific role. For example, various other molecules—including lysophosphatidylcholine and the nucleotides ATP and UTP—act as ‘find me’ signals that attract phagocytes towards apoptotic cells (Hochreiter-Hufford and Ravichandran, 2013). Another example is an iron-binding glycoprotein called lactoferrin that inhibits the translocation of certain white blood cells, thereby apparently contributing to the anti-inflammatory effect of apoptosis (Bournazou et al., 2009).

To what extent do the soluble molecules released by apoptotic cells have an effect on cells remote from the site of death? And how does the contribution of these molecules to the anti-inflammatory consequences of apoptosis compare with the contribution that results from direct contact between the dying cell and the cell engulfing it? Nagata and co-workers report that in a mouse model of inflammation (zymosan-induced peritonitis), deletion of either the Pannexin-1 gene or the A2a gene prolongs the inflammation. These findings support the notion that (in this experimental model) adenosine derived from apoptotic cells contributes significantly to the restriction of inflammation. More precise cell-type-specific targeting of these molecules (and other molecules that have anti-inflammatory effects) should lead to an improved understanding of their relative contributions to immune regulation in specific pathological situations.

References

-

Apoptotic human cells inhibit migration of granulocytes via release of lactoferrinJournal of Clinical Investigation 119:20–32.https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI36226

-

Clearing the dead: apoptotic cell sensing, recognition, engulfment, and digestionCold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 5:a008748.https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a008748

-

Phosphatidylserine-dependent ingestion of apoptotic cells promotes TGF-beta1 secretion and the resolution of inflammationJournal of Clinical Investigation 109:41–50.https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI11638

-

Apoptosis: a basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in tissue kineticsBritish Journal of Cancer 26:239–257.https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.1972.33

-

The inflammatory response to cell deathAnnual Reviews of Pathology 3:99–126.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.151456

-

The ‘danger’ sensors that STOP the immune response: the A2 adenosine receptors?Trends in Immunology 26:299–304.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2005.04.004

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: March 25, 2014 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2014, Wallach and Kovalenko

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 5,018

- views

-

- 210

- downloads

-

- 20

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Cancer Biology

- Cell Biology

Collective cell migration is fundamental for the development of organisms and in the adult for tissue regeneration and in pathological conditions such as cancer. Migration as a coherent group requires the maintenance of cell–cell interactions, while contact inhibition of locomotion (CIL), a local repulsive force, can propel the group forward. Here we show that the cell–cell interaction molecule, N-cadherin, regulates both adhesion and repulsion processes during Schwann cell (SC) collective migration, which is required for peripheral nerve regeneration. However, distinct from its role in cell–cell adhesion, the repulsion process is independent of N-cadherin trans-homodimerisation and the associated adherens junction complex. Rather, the extracellular domain of N-cadherin is required to present the repulsive Slit2/Slit3 signal at the cell surface. Inhibiting Slit2/Slit3 signalling inhibits CIL and subsequently collective SC migration, resulting in adherent, nonmigratory cell clusters. Moreover, analysis of ex vivo explants from mice following sciatic nerve injury showed that inhibition of Slit2 decreased SC collective migration and increased clustering of SCs within the nerve bridge. These findings provide insight into how opposing signals can mediate collective cell migration and how CIL pathways are promising targets for inhibiting pathological cell migration.

-

- Cell Biology

- Neuroscience

Alternative RNA splicing is an essential and dynamic process in neuronal differentiation and synapse maturation, and dysregulation of this process has been associated with neurodegenerative diseases. Recent studies have revealed the importance of RNA-binding proteins in the regulation of neuronal splicing programs. However, the molecular mechanisms involved in the control of these splicing regulators are still unclear. Here, we show that KIS, a kinase upregulated in the developmental brain, imposes a genome-wide alteration in exon usage during neuronal differentiation in mice. KIS contains a protein-recognition domain common to spliceosomal components and phosphorylates PTBP2, counteracting the role of this splicing factor in exon exclusion. At the molecular level, phosphorylation of unstructured domains within PTBP2 causes its dissociation from two co-regulators, Matrin3 and hnRNPM, and hinders the RNA-binding capability of the complex. Furthermore, KIS and PTBP2 display strong and opposing functional interactions in synaptic spine emergence and maturation. Taken together, our data uncover a post-translational control of splicing regulators that link transcriptional and alternative exon usage programs in neuronal development.