Development: Computing away the magic?

Multicellular organisms employ a variety of mechanisms to ensure that genes are expressed at the right time and place throughout their life cycles. The transcription of DNA into RNA is augmented by activators and diminished by repressors. Both classes of regulatory proteins bind to specific sequences contained within enhancers, which are the key agents of gene regulation in higher organisms. Elucidating how enhancers work is critical for understanding gene regulation in development and disease.

It is over 30 years since Banerji and Schaffner discovered that enhancers can be physically separate from the genes they regulate (Banerji et al., 1981). Enhancers can map quite far—1 million base pairs or more—from their target genes (Amano et al., 2009). This action at a distance is a defining property of complex organisms, and contrasts with what happens in simple bacteria, where most activator and repressor binding sites are found quite close to their target genes (see, e.g., Levine and Tjian, 2003).

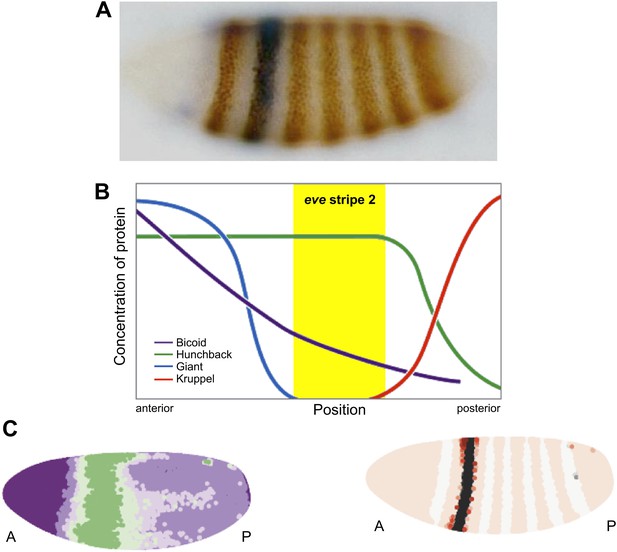

One of the most widely studied enhancers is the eve stripe 2 enhancer in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster (Small et al., 1992). The body of the Drosophila embryo is made up of 14 segments, and a gene called eve (even-skipped) is expressed in the even-numbered segments, giving rise to a distinctive pattern of seven stripes (Figure 1A). It was initially thought that the long-range diffusion of morphogens (Turing, 1952)—signaling molecules that influence tissue development through their formation of concentration gradients—coordinated the expression of all seven eve stripes (Meinhardt, 1986). The discovery that eve stripe 2 had its own dedicated enhancer led one researcher to complain of the ‘inelegance’ of such a mechanism (Akam, 1989). However, we have now come full circle: I cannot help but complain that the new models for the regulation of eve expression described by Nicholas Luscombe and co-workers in eLife seem to strip the mystique from the eve stripe 2 enhancer (Ilsley et al., 2013).

Regulation of eve stripe 2. The gene eve is expressed in the even-numbered body segments of Drosophila embryos, giving rise to a distinctive pattern of stripes. A, Transgenic embryo expressing an eve.2>lacZ fusion gene. The endogenous eve stripes are stained brown, while stripe 2 is stained blue (Small et al., 1992). B, The transcription factors Krüppel and Giant (repressors) and Bicoid and Hunchback (activators) are expressed in distinct patterns along the Drosophila embryo, and their combined effects dictate the position of eve stripe 2 (Watson et al., 2014). C, Computer simulations can be used to model the expression gradient of Bicoid (left) and the resulting effect on the position of eve stripe 2 (right). A, anterior; P, posterior.

The stripe 2 enhancer is regulated by four different transcription factors in the early Drosophila embryo—two activators, Bicoid and Hunchback; and two repressors, Giant and Krüppel (Small et al., 1992). There are 12 binding sites for these transcription factors distributed over the length of the enhancer, and the combined effects of these four proteins dictate the location of the second eve stripe (Figure 1B). In principle, Bicoid and Hunchback can activate the eve stripe 2 enhancer in the entire anterior half of the embryo (from the head to the anterior thorax); however, localized repressors—Giant and Krüppel—delineate eve expression within the stripe 2 domain.

Luscombe and co-workers—including Garth Ilsley as first author—investigated how these four transcription factors produce the stripe 2 expression pattern (Figure 1B), by combining quantitative imaging with computer simulations of different mathematical models. They used this same approach to model the enhancer that regulates stripes 3 and 7, but for simplicity I will restrict my discussion to stripe 2. The resulting models provide new insights into the mechanisms of stripe formation during development. First, IIsley et al. argue that the order of the Bicoid, Hunchback, Giant and Krüppel binding sites is unlikely to be important for stripe 2 expression. They base this on the observation that models in which the effects of activators can simply be added to those of repressors are sufficient to produce the stripe 2 pattern, and there is no need to assume that activators bound to adjacent sites cooperate with each other to augment their activities. Moreover, there is no indication of nonlinear effects such as ‘repression dominance’, whereby repressors downregulate transcription more than activators upregulate it (Arnosti et al., 1996). Rather, the models call for a simple balance between the effects of activators and those of repressors.

The most interesting implication of this work is that Bicoid might not function solely as an activator (Driever et al., 1989; Struhl et al., 1989). Luscombe and co-workers were able to achieve more faithful simulations of the stripe 2 expression pattern by assuming that Bicoid, which is most abundant in the anterior region of the embryo and gradually declines in concentration towards the posterior end, acts as both an activator and a repressor. Ilsley et al. propose that high levels of Bicoid repress expression of stripe 2 in anterior regions, while lower levels in the more central regions activate its expression (Figure 1C).

The idea that a transcription factor can mediate both activation and repression is not new. However, this is the first time that such a dual mechanism has been suggested for Bicoid, the lynchpin of anterior–posterior patterning. This dual function of Bicoid can explain why eve, and many other segmentation genes, are silent at the anterior pole of the Drosophila embryo (Andrioli et al., 2002).

In summary, the eve stripe 2 enhancer produces an exquisite on/off pattern of expression in response to crude gradients of transcription factors, and its ability to do so has previously been explained by nonlinear interactions between proteins. By arguing against such nonlinearity, Ilsley et al. seemingly strip the magic from the stripe 2 enhancer. But is the magic really gone? How the enhancer determines whether Bicoid functions as an activator or a repressor is uncertain. Hence, I believe that the concept of the enhancer as a template for weak protein interactions is alive and well, and yes, still a mystery.

References

-

Anterior repression of a Drosophila stripe enhancer requires three position-specific mechanismsDevelopment 129:4931–4940.

-

The gap protein knirps mediates both quenching and direct repression in the Drosophila embryoEMBO J 15:3659–3666.

-

The Chemical Basis of MorphogenesisPhil Trans Royal Soc London Series B 237:37–72.https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1952.0012

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: August 6, 2013 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2013, Levine

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,245

- views

-

- 81

- downloads

-

- 6

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Developmental Biology

- Structural Biology and Molecular Biophysics

The receptor tyrosine kinase ROR2 mediates noncanonical WNT5A signaling to orchestrate tissue morphogenetic processes, and dysfunction of the pathway causes Robinow syndrome, Brachydactyly B and metastatic diseases. The domain(s) and mechanisms required for ROR2 function, however, remain unclear. We solved the crystal structure of the extracellular cysteine-rich (CRD) and Kringle (Kr) domains of ROR2 and found that, unlike other CRDs, the ROR2 CRD lacks the signature hydrophobic pocket that binds lipids/lipid-modified proteins, such as WNTs, suggesting a novel mechanism of ligand reception. Functionally, we showed that the ROR2 CRD, but not other domains, is required and minimally sufficient to promote WNT5A signaling, and Robinow mutations in the CRD and the adjacent Kr impair ROR2 secretion and function. Moreover, using function-activating and -perturbing antibodies against the Frizzled (FZ) family of WNT receptors, we demonstrate the involvement of FZ in WNT5A-ROR signaling. Thus, ROR2 acts via its CRD to potentiate the function of a receptor super-complex that includes FZ to transduce WNT5A signals.

-

- Developmental Biology

- Immunology and Inflammation

Cardiac macrophages are heterogenous in phenotype and functions, which has been associated with differences in their ontogeny. Despite extensive research, our understanding of the precise role of different subsets of macrophages in ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury remains incomplete. We here investigated macrophage lineages and ablated tissue macrophages in homeostasis and after I/R injury in a CSF1R-dependent manner. Genomic deletion of a fms-intronic regulatory element (FIRE) in the Csf1r locus resulted in specific absence of resident homeostatic and antigen-presenting macrophages, without affecting the recruitment of monocyte-derived macrophages to the infarcted heart. Specific absence of homeostatic, monocyte-independent macrophages altered the immune cell crosstalk in response to injury and induced proinflammatory neutrophil polarization, resulting in impaired cardiac remodeling without influencing infarct size. In contrast, continuous CSF1R inhibition led to depletion of both resident and recruited macrophage populations. This augmented adverse remodeling after I/R and led to an increased infarct size and deterioration of cardiac function. In summary, resident macrophages orchestrate inflammatory responses improving cardiac remodeling, while recruited macrophages determine infarct size after I/R injury. These findings attribute distinct beneficial effects to different macrophage populations in the context of myocardial infarction.