Antimicrobials: A lysin to kill

Being in the right place at the right time is a recipe for success for an antibacterial compound. Streptococcus pyogenes (often simply called Spy) is a bacterium that is responsible for a range of human infections, from the common “strep throat” to necrotizing fasciitis, the life-threatening condition also known as “flesh-eating disease” (Ralph and Carapetis, 2013). Spy infections can often return after treatment because the bacteria can invade human cells, which protect them from both our immune system and antibiotics (Osterlund et al., 1997). Now, in eLife, Daniel Nelson from the University of Maryland and co-workers – including Yang Shen (Maryland) and Marilia Barros (Carnegie Mellon University) as joint first authors – report the unexpected ability of an antimicrobial enzyme called PlyC to find and kill Spy that is hiding inside human cells (Shen et al., 2016).

PlyC is produced by a bacteriophage, a virus that infects bacterial cells. Like all viruses, bacteriophages commandeer their host’s replication machinery to produce copies of themselves. Some bacteriophages also carry genes for enzymes called endolysins or phage lysins that allow them to escape from the bacteria they have invaded by degrading the mesh-like cell wall that protects each bacterial cell.

The medical potential of bacteriophages and phage lysins was recognized shortly after they were discovered over a century ago. In fact, bacteriophage treatment was used for a range of illnesses in the early 20th Century (Chanishvili, 2012), but it was quickly overshadowed by small-molecule antibiotics from the 1940s onwards. The widespread use of antibiotics in medicine and agriculture has, unfortunately and inevitably, led to the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and a possible end to the “Antibiotic Era” (Harrison and Svec, 1998; Boucher et al., 2009). Also, more people are now aware that using broad-spectrum antimicrobial drugs can alter the microbial community in the gut, which in turn can impact on human health (Cotter et al., 2012).

Phage lysins possess a number of good antimicrobial traits. They are potent, fast-acting, specific to a narrow range of bacteria and relatively harmless to other types of cells. They can also kill bacteria that are dormant or not actively growing (Fischetti, 2010), and have been used to cure short-term Spy infections in mice (Gilmer et al., 2013). However, most had assumed that these enzymes were incapable of entering into host cells, and unlikely to be useful for treating chronic Spy infections in humans.

Shen, Barros and colleagues, who are based at various centers across the United States, attempted to overcome this assumed limitation by fusing phage lysins with fragments of proteins that help transport other molecules through cell membranes. Serendipitously, they discovered that PlyC is intrinsically active against intracellular Spy. PlyC is the only known phage lysin that is composed of two subunits. One of these subunits (PlyCA) is enzymatically active and degrades the bacterial cell wall. The other subunit (PlyCB) binds to the Spy cell surface and, as discovered by Shen, Barros et al., is needed to get the enzyme inside a human epithelial cell (Figure 1).

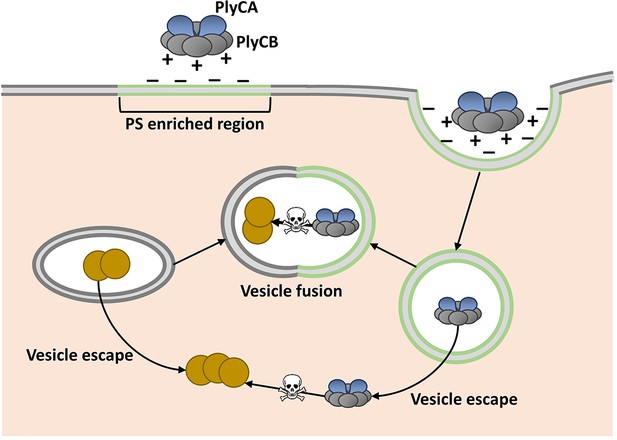

Model showing how the enzyme PlyC can enter human epithelial cells and kill intracellular Streptococcus pyogenes (Spy).

PlyC is composed of two subunits. PlyCB forms an eight-part ring that normally binds to the Spy cell surface. PlyCA is the enzymatically active subunit that degrades the bacterial cell wall. The PlyCB surface is normally positively charged, and Shen, Barros et al. show that it interacts with phosphatidylserine (PS), which is negatively charged. They propose that PlyCB binds to lipid rafts (shown in green) that are enriched in PS; this causes the membrane to fold around PlyC, which ultimately enters the cell inside a vesicle. These vesicles may fuse with bacteria-containing vesicles, giving PlyC access to intracellular Spy (depicted as brown circles). Alternatively, PlyC may escape the vesicle and interact with and kill Spy that is free in the host cell.

The PlyCB subunit was known to have a positively charged surface (McGowan et al., 2012), and so Shen, Barros et al. hypothesized that it interacts with negatively charged components of the cell membrane. Indeed, they then went on to discover that PlyCB binds to a negatively charged molecule called phosphatidylserine that is common in eukaryotic cell membranes. Their results also suggested that PlyCB can only penetrate membranes that contain at least 30% phosphatidylserine.

Regions of the cell membrane called lipid rafts have high levels of phosphatidylserine, and are involved in the uptake of numerous molecules from the cell’s exterior via a process called endocytosis (Pike, 2009). This suggested that PlyC might enter cells via an endocytic mechanism, and Shen, Barros et al. provided further support for this idea by showing that PlyCB co-localizes with another protein that binds to lipid rafts. Based on these data and some molecular modeling, they proposed that PlyCB binds to phosphatidylserine, causes the membrane to fold around it, and ultimately enters the cell via endocytosis (Figure 1).

These new findings demonstrate the potential of phage lysins, and possibly bacteriophage-based therapy, to treat challenging bacterial infections. Specifically, they also highlight the potential of PlyC to reduce or even prevent infection with Spy, which remains a major health concern in low- to middle-income countries and disproportionately targets children (Ralph and Carapetis, 2013). Further work is needed to confirm if PlyC enters cells via lipid raft-mediated endocytosis, and to determine how PlyC ultimately meets the intracellular Spy in order to kill it. However, insights provided by Shen, Barros et al. open up the possibility of engineering new endolysins based on PlyCB to target other disease-causing microbes that evade the immune system by hiding in an infected person’s cells.

References

-

Bad bugs, no drugs: no ESKAPE! An update from the Infectious Diseases Society of AmericaClinical Infectious Diseases 48:1–12.https://doi.org/10.1086/595011

-

The impact of antibiotics on the gut microbiota as revealed by high throughput DNA sequencingDiscovery Medicine 13:193–199.

-

Bacteriophage endolysins: a novel anti-infective to control Gram-positive pathogensInternational Journal of Medical Microbiology 300:357–362.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmm.2010.04.002

-

Novel bacteriophage lysin with broad lytic activity protects against mixed infection by Streptococcus pyogenes and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureusAntimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 57:2743–2750.https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02526-12

-

The beginning of the end of the antibiotic era? Part I. The problem: Abuse of the "miracle drugs"Quintessence International 29:151–162.

-

X-ray crystal structure of the streptococcal specific phage lysin PlyCProceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109:12752–12757.https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1208424109

-

The challenge of lipid raftsJournal of Lipid Research 50 Suppl:S323–328.https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.R800040-JLR200

-

Group a streptococcal diseases and their global burdenCurrent Topics in Microbiology and Immunology 368:1–27.https://doi.org/10.1007/82_2012_280

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: April 27, 2016 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2016, Gaca et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,987

- views

-

- 254

- downloads

-

- 3

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Biochemistry and Chemical Biology

Transporter research primarily relies on the canonical substrates of well-established transporters. This approach has limitations when studying transporters for the low-abundant micromolecules, such as micronutrients, and may not reveal physiological functions of the transporters. While d-serine, a trace enantiomer of serine in the circulation, was discovered as an emerging biomarker of kidney function, its transport mechanisms in the periphery remain unknown. Here, using a multi-hierarchical approach from body fluids to molecules, combining multi-omics, cell-free synthetic biochemistry, and ex vivo transport analyses, we have identified two types of renal d-serine transport systems. We revealed that the small amino acid transporter ASCT2 serves as a d-serine transporter previously uncharacterized in the kidney and discovered d-serine as a non-canonical substrate of the sodium-coupled monocarboxylate transporters (SMCTs). These two systems are physiologically complementary, but ASCT2 dominates the role in the pathological condition. Our findings not only shed light on renal d-serine transport, but also clarify the importance of non-canonical substrate transport. This study provides a framework for investigating multiple transport systems of various trace micromolecules under physiological conditions and in multifactorial diseases.

-

- Biochemistry and Chemical Biology

- Cell Biology

Mediator of ERBB2-driven Cell Motility 1 (MEMO1) is an evolutionary conserved protein implicated in many biological processes; however, its primary molecular function remains unknown. Importantly, MEMO1 is overexpressed in many types of cancer and was shown to modulate breast cancer metastasis through altered cell motility. To better understand the function of MEMO1 in cancer cells, we analyzed genetic interactions of MEMO1 using gene essentiality data from 1028 cancer cell lines and found multiple iron-related genes exhibiting genetic relationships with MEMO1. We experimentally confirmed several interactions between MEMO1 and iron-related proteins in living cells, most notably, transferrin receptor 2 (TFR2), mitoferrin-2 (SLC25A28), and the global iron response regulator IRP1 (ACO1). These interactions indicate that cells with high MEMO1 expression levels are hypersensitive to the disruptions in iron distribution. Our data also indicate that MEMO1 is involved in ferroptosis and is linked to iron supply to mitochondria. We have found that purified MEMO1 binds iron with high affinity under redox conditions mimicking intracellular environment and solved MEMO1 structures in complex with iron and copper. Our work reveals that the iron coordination mode in MEMO1 is very similar to that of iron-containing extradiol dioxygenases, which also display a similar structural fold. We conclude that MEMO1 is an iron-binding protein that modulates iron homeostasis in cancer cells.