Language: I see what you are saying

In the mid-1940s, the psychologist Alvin Liberman went to work with Franklin Cooper at the Haskins Laboratories in New Haven, Connecticut. He initially set out to create a device to turn printed letters into sounds so that blind people could ‘hear’ written texts (Liberman, 1996). His first foray involved shining a light through a slit onto the page in order to convert the lines of each letter into light and then into frequencies of sound. Liberman and colleagues reasoned that with enough training, blind users would be able to learn these arbitrary letter-sound pairs and so be able to understand the text.

The device was a spectacular failure: the users performed slowly and inaccurately. This led Liberman and colleagues to the realization that speech is not an arbitrary sequence of sounds, but a specific human code. They argued that the key to this code was the link between the speech sounds a person hears and the motor actions they make in order to speak. This important work led to decades of further research and helped lay the foundation for the psychological and neuroscientific study of speech.

When we watch and listen to someone speak, our brain combines the visual information of the movement of the speaker’s mouth with the speech sounds that are produced by this movement (McGurk and MacDonald, 1976). One of the core problems that researchers in this field are investigating is how these different sets of information are integrated to allow us to understand speech. Now, in eLife, Hyojin Park, Christoph Kayser, Gregor Thut and Joachim Gross of the University of Glasgow report that they have studied this integration by using a technique called magnetoencephalography to record the magnetic fields that are generated by the electrical currents of the brain (Park et al., 2016).

Park et al. presented volunteers with audio-visual clips of naturalistic speech and then asked them to complete a short questionnaire about the speech they heard and saw. In some cases, these clips were manipulated so that the audio did not match the video. In other cases, Park et al. presented a different speech signal to each ear and asked the volunteers to pay attention to just one signal. By analyzing these combinations, they could separate the brain activity that is associated with watching someone speak from the activity that processes the speech sounds themselves.

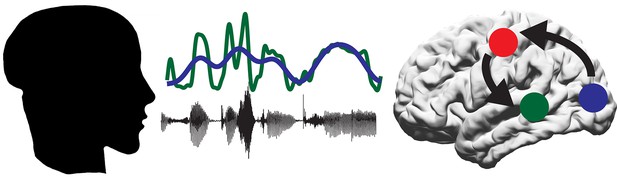

Park et al. found that a part of the continuous speech stream called the envelope, which is the slow rising and falling in the amplitude of the speech, was tracked in auditory areas of the brain (Figure 1). Conversely, the visual cortex tracked mouth movements. These results are a good replication and extension of previous data recorded from both the auditory domain (Cogan and Poeppel, 2011; Gross et al., 2013; Luo and Poeppel, 2007) and the visual domain (Luo et al., 2010; Zion Golumbic et al., 2013). However, Park et al. extended these findings by asking: what role does tracking the lip movements of a speaker play in speech perception?

A proposed model for the role of the motor system in speech perception.

A person produces speech by the coordinated movement of their articulatory system. The listener hears the sound (black line) and sees the mouth of the speaker open and close (represented by blue line). Some of the information in the sound is contained within the speech envelope (green line). The auditory regions of the brain (green circle) track the speech envelope, while the visual system (blue circle) tracks the visual movements of the mouth. The motor system (red circle) then decodes the intended mouth movement and integrates this with the response of the auditory regions to the incoming sounds.

To learn more about which parts of the brain track the lip movements of the speaker, Park et al. performed a partial regression on the lip movement, envelope and brain activity data to remove the response to sound and focus on just the effect of tracking the lip movements. This revealed two areas of the brain that actively track lip movements during speech. The first area, as found by previous researchers, was the visual cortex. This presumably tracks the lips as a visual signal. The second area was the left motor cortex.

To further establish the role of the motor cortex during speech perception, Park et al. examined the comprehension scores from the questionnaire. These scores could be predicted from the extent to which neural activity in the motor cortex synchronized with the lip movements observed by the participant: higher scores correlated with a higher degree of synchronization. This suggests that the ability of the motor cortex to track lip movements is important for understanding audiovisual speech, suggesting a new role for the motor system in speech perception. Park et al. interpret this finding to suggest that the motor system helps to predict the upcoming sound signal by simulating the speaker’s intended mouth movement (Arnal and Giraud, 2012; Figure 1).

While this is an important first step, it is still not clear how the lip movement tracked by the motor cortex is integrated with the response of auditory regions of the brain to speech sounds. Are mouth movements tracked specifically for ambiguous or difficult stimuli (Du et al., 2014) or is this tracking necessary for perceiving speech generally? Future work will hopefully clarify the specifics of this mechanism.

It is interesting and somewhat ironic that the motor cortex tracks the visual signals of mouth movement, given the early (and unsuccessful) efforts of Liberman and colleagues to help the blind ‘hear’ written texts. Indeed, just as these early researchers proposed, it seems that the link between the motor and auditory system is a key to understanding how speech is represented in the brain.

References

-

Cortical oscillations and sensory predictionsTrends in Cognitive Sciences 16:390–398.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2012.05.003

-

A mutual information analysis of neural coding of speech by low-frequency MEG phase informationJournal of Neurophysiology 106:554–563.https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00075.2011

-

Noise differentially impacts phoneme representations in the auditory and speech motor systemsProceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111:7126–7131.https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1318738111

-

Visual input enhances selective speech envelope tracking in auditory cortex at a "cocktail party"Journal of Neuroscience 33:1417–1426.https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3675-12.2013

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: June 9, 2016 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2016, Cogan

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,592

- views

-

- 131

- downloads

-

- 0

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Neuroscience

Cholecystokinin (CCK) is an essential modulator for neuroplasticity in sensory and emotional domains. Here, we investigated the role of CCK in motor learning using a single pellet reaching task in mice. Mice with a knockout of Cck gene (Cck−/−) or blockade of CCK-B receptor (CCKBR) showed defective motor learning ability; the success rate of retrieving reward remained at the baseline level compared to the wildtype mice with significantly increased success rate. We observed no long-term potentiation upon high-frequency stimulation in the motor cortex of Cck−/− mice, indicating a possible association between motor learning deficiency and neuroplasticity in the motor cortex. In vivo calcium imaging demonstrated that the deficiency of CCK signaling disrupted the refinement of population neuronal activity in the motor cortex during motor skill training. Anatomical tracing revealed direct projections from CCK-expressing neurons in the rhinal cortex to the motor cortex. Inactivation of the CCK neurons in the rhinal cortex that project to the motor cortex bilaterally using chemogenetic methods significantly suppressed motor learning, and intraperitoneal application of CCK4, a tetrapeptide CCK agonist, rescued the motor learning deficits of Cck−/− mice. In summary, our results suggest that CCK, which could be provided from the rhinal cortex, may surpport motor skill learning by modulating neuroplasticity in the motor cortex.

-

- Neuroscience

Probing memory of a complex visual image within a few hundred milliseconds after its disappearance reveals significantly greater fidelity of recall than if the probe is delayed by as little as a second. Classically interpreted, the former taps into a detailed but rapidly decaying visual sensory or ‘iconic’ memory (IM), while the latter relies on capacity-limited but comparatively stable visual working memory (VWM). While iconic decay and VWM capacity have been extensively studied independently, currently no single framework quantitatively accounts for the dynamics of memory fidelity over these time scales. Here, we extend a stationary neural population model of VWM with a temporal dimension, incorporating rapid sensory-driven accumulation of activity encoding each visual feature in memory, and a slower accumulation of internal error that causes memorized features to randomly drift over time. Instead of facilitating read-out from an independent sensory store, an early cue benefits recall by lifting the effective limit on VWM signal strength imposed when multiple items compete for representation, allowing memory for the cued item to be supplemented with information from the decaying sensory trace. Empirical measurements of human recall dynamics validate these predictions while excluding alternative model architectures. A key conclusion is that differences in capacity classically thought to distinguish IM and VWM are in fact contingent upon a single resource-limited WM store.