Membrane Phase Separation: Localizing order to boost signaling

Biological membranes generally consist of a lipid bilayer that has various receptors and other proteins embedded within it. The lipids in the membrane may be organized into one of two phases: liquid-disordered and liquid-ordered (Simons and Ikonen, 1997). The current view is that most of the membrane is in the liquid-disordered phase; the liquid-ordered regions are small (typically about 20 nanometers across) and span both layers of the membrane (Eggeling et al., 2009; Raghupathy et al., 2015).

Liquid-ordered domains can act as signaling platforms to activate immune cells (Stefanova et al., 1991). In B cells, for example, liquid-ordered domains are recruited to B cell receptors when antigens bind to the receptors: the presence of these domains helps a kinase called Lyn to phosphorylate the receptor, which accelerates the signaling process (Sohn et al., 2006). Now, in eLife, Sarah Veatch and colleagues at the University of Michigan – including Matthew Stone and Sarah Shelby as joint first authors – report how the clustering of B cell receptors (BCRs) creates a membrane domain similar to previously observed liquid-ordered phases, but over a larger area, which helps to activate the receptors (Stone et al., 2017).

Stone et al. used two-color super-resolution microscopy to characterize the lipid environment in the vicinity of the BCR clusters. To visualize the different phases, the ordered and disordered domains were marked with different lipid-linked or transmembrane peptide probes (shortened versions of proteins that are normally found in the cell membrane) linked to a photoactivatable fluorescent protein. Cross-correlation analysis (Sengupta et al., 2011) revealed that liquid-ordered domains are enriched (and hence liquid-disordered domains are depleted) in an area around the clusters. The ordered domains also recruit the Lyn kinase to phosphorylate the receptors, and exclude an enzyme called CD45 (which removes phosphate groups).

The cross-correlation analysis method used by Stone et al. has several advantages over other methods for analyzing images of membranes that contain physiological densities of receptors and low densities of probes (which is necessary to avoid disrupting the lipid phases). For example, it is not susceptible to “over-counting” artifacts related to fluorophore blinking. However, one caveat of this study is that the magnitude of the correlations is quite low, such that the experimental distributions are not far from random patterns. Additional confidence might be gained from coordinate-based co-localization analysis (Malkusch et al., 2012) that provides a nearest neighbor distance, and coclustering methods (Rossy et al., 2014) that provide a co-localization score.

How do the cross-correlation values relate to visual experience? Cross-correlation (Cr) coefficients for B cell antigen receptor with phosphotyrosine (Cr = 8) or with Lyn (Cr = 3) are readily or moderately obvious in images, respectively. In contrast, the Cr values of around 0.8 or 1.2 that are respectively associated with the phase probes labeling the liquid-disordered and liquid-ordered phases near B cell antigen receptor clusters are not readily detected by eye. So the axiom of “seeing is believing” is not applicable.

The cross-correlations can be used to calculate energies needed to account for the non-random organization. The calculated energy is consistent with a moderate restriction on the lateral movement of the receptor through a membrane. Comparing how the peptide phase probes used to mark the liquid-ordered and liquid-disordered phases localize compared with their full length protein counterparts suggests that less than half of the energy involved in recruiting Lyn to B cell antigen receptor clusters is accounted for through effects in the lipid phase. The location of CD45 is influenced by steric clashes with its large extracellular domain (Chang et al., 2016) or the exclusion of its cytoplasmic domain from protein driven phases (Su et al., 2016). However, Stone et al. conclude that all the energy for CD45 exclusion induced by B cell antigen receptor cross-linking comes from membrane phase separation.

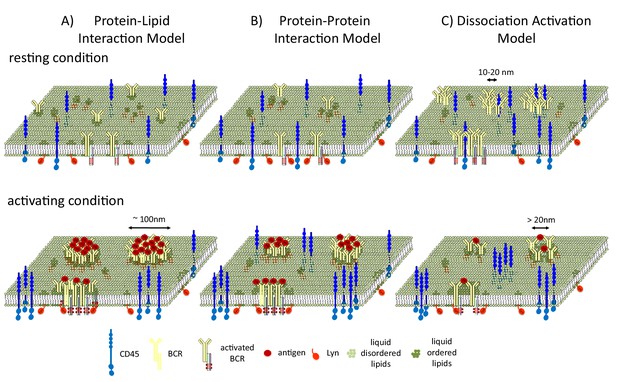

Stone et al. present a minimal model for predicting how membrane phase behavior influences B cell signaling. In this model, the clustering of the receptors stabilizes an extended liquid-ordered domain. This domain then recruits Lyn and excludes CD45, leading to the phosphorylation of the receptor (Figure 1A).

B cell receptors and liquid-ordered domains.

(A) In the model proposed by Stone et al., B cell receptors (BCRs) cluster and intrinsically interact with liquid-ordered domains. The interaction of the receptors with antigens (Ag) stabilizes an extended liquid-ordered domain (around 100 nanometers in diameter) through protein-lipid interactions that recruit kinases (such as Lyn) and exclude phosphatases (such as CD45). (B) In an alternative protein-protein interaction model, B cell receptors do not interact with liquid-ordered domains, but antigen binding causes the receptors to cluster. This initiates interactions between the receptors and lipid-modified kinases, which then recruit liquid-ordered domains that provide further feed forward effects, such as CD45 exclusion, to allow efficient phosphorylation. (C) In the dissociation activation model, the receptors cluster to produce a structure in which kinases cannot access the sites they would normally phosphorylate. The binding of antigens to the receptors disrupts the clusters, leading to the recruitment of kinases and the formation of looser clusters that resemble liquid-ordered domains.

Two alternative models have also been used to describe how liquid-ordered domains affect signaling. In the protein-protein interaction model, BCR clustering recruits Lyn, and Lyn then recruits the liquid-ordered domain (Figure 1B). In the dissociation activation model, antigen binding to the receptor disrupts pre-existing clusters (Kläsener et al., 2014). Cluster disruption may also change the lipid environment by allowing more space for the ordered domains (which are around 20 nanometers in diameter) to penetrate into the looser clusters (Figure 1C), which may also be regulated by F-actin mediated restraints (Treanor et al., 2011).

The work of Stone et al. opens up the possibility that lipid phase-like domains may regulate a broad range of signaling pathways. Furthermore, the coupling of localization microscopy and cross-correlation could be extended to investigate other systems – both in the immune system (such as T cell receptors) and beyond. Thus, Stone et al. have entered into a realm of analysis of the seemingly invisible that would give many pause, yet extends the power of localization microscopy to reveal new biology.

References

-

Initiation of T cell signaling by CD45 segregation at 'close contacts'Nature Immunology 17:574–582.https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.3392

-

Coordinate-based colocalization analysis of single-molecule localization microscopy dataHistochemistry and Cell Biology 137:1–10.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00418-011-0880-5

-

Method for co-cluster analysis in multichannel single-molecule localisation dataHistochemistry and Cell Biology 141:605–612.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00418-014-1208-z

-

Dynamic cortical actin remodeling by ERM proteins controls BCR microcluster organization and integrityThe Journal of Experimental Medicine 208:1055–1068.https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20101125

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: March 30, 2017 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2017, Bálint et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 2,163

- views

-

- 338

- downloads

-

- 12

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Structural Biology and Molecular Biophysics

Roco proteins entered the limelight after mutations in human LRRK2 were identified as a major cause of familial Parkinson’s disease. LRRK2 is a large and complex protein combining a GTPase and protein kinase activity, and disease mutations increase the kinase activity, while presumably decreasing the GTPase activity. Although a cross-communication between both catalytic activities has been suggested, the underlying mechanisms and the regulatory role of the GTPase domain remain unknown. Several structures of LRRK2 have been reported, but structures of Roco proteins in their activated GTP-bound state are lacking. Here, we use single-particle cryo-electron microscopy to solve the structure of a bacterial Roco protein (CtRoco) in its GTP-bound state, aided by two conformation-specific nanobodies: NbRoco1 and NbRoco2. This structure presents CtRoco in an active monomeric state, featuring a very large GTP-induced conformational change using the LRR-Roc linker as a hinge. Furthermore, this structure shows how NbRoco1 and NbRoco2 collaborate to activate CtRoco in an allosteric way. Altogether, our data provide important new insights into the activation mechanism of Roco proteins, with relevance to LRRK2 regulation, and suggest new routes for the allosteric modulation of their GTPase activity.

-

- Developmental Biology

- Structural Biology and Molecular Biophysics

A crucial event in sexual reproduction is when haploid sperm and egg fuse to form a new diploid organism at fertilization. In mammals, direct interaction between egg JUNO and sperm IZUMO1 mediates gamete membrane adhesion, yet their role in fusion remains enigmatic. We used AlphaFold to predict the structure of other extracellular proteins essential for fertilization to determine if they could form a complex that may mediate fusion. We first identified TMEM81, whose gene is expressed by mouse and human spermatids, as a protein having structural homologies with both IZUMO1 and another sperm molecule essential for gamete fusion, SPACA6. Using a set of proteins known to be important for fertilization and TMEM81, we then systematically searched for predicted binary interactions using an unguided approach and identified a pentameric complex involving sperm IZUMO1, SPACA6, TMEM81 and egg JUNO, CD9. This complex is structurally consistent with both the expected topology on opposing gamete membranes and the location of predicted N-glycans not modeled by AlphaFold-Multimer, suggesting that its components could organize into a synapse-like assembly at the point of fusion. Finally, the structural modeling approach described here could be more generally useful to gain insights into transient protein complexes difficult to detect experimentally.