Pregnancy Loss: A possible link between olfaction and miscarriage

Unexplained repeated pregnancy loss is a poorly understood condition that can cause significant distress and for which no effective treatment exists. Much research to date has focused on dysfunctions of the uterus or hormonal signaling (Saravelos and Regan, 2014), but the possible involvement of the nervous system has not been explored despite the role of the olfactory system in mammalian reproduction being well-documented (Dulac and Torello, 2003).

Exposing female rodents to the smell of adult males can lead to synchronized menstrual cycling (Whitten, 1956) and accelerated sexual maturation (Vandenbergh, 1967), as well as to embryos failing to implant in the uterus (Bruce, 1959). Olfactory cues might also play a role in human reproduction: for instance, the menstrual cycle phase may influence preferences for male odors (Rantala et al., 2006). This presents the possibility that altered neural processing of socially relevant odors, such as the scent of a partner, may be linked to pregnancy loss and other reproductive disorders. Now, in eLife, Noam Sobel (Weizmann Institute of Science) and colleagues – including Liron Rozenkrantz, Reut Weissgross and Tali Weiss as joint first authors – report that women who have experienced unexplained repeated pregnancy loss process the odors of males differently (Rozenkrantz et al., 2020).

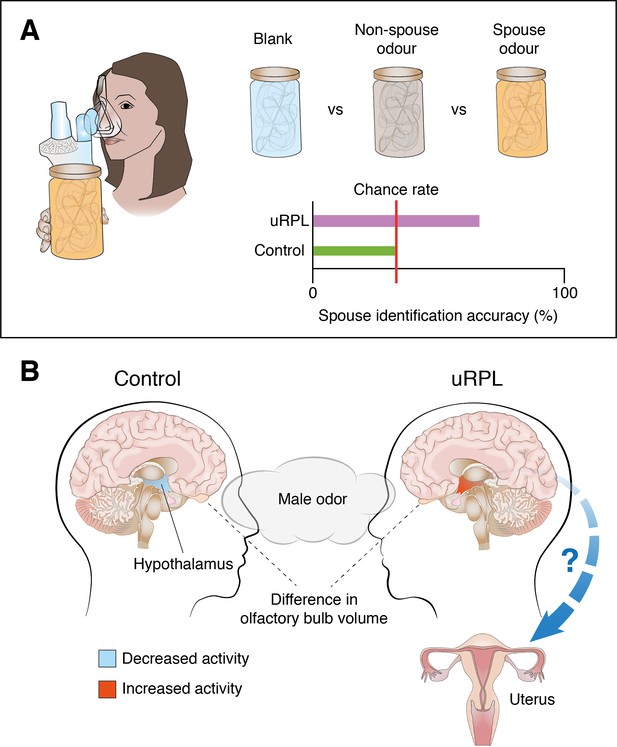

The researchers started by measuring the ability of women to discern the body odor of their spouse when presented with three choices – a blank odor, their spouse's odor and a non-spouse odor. Women who had experienced unexplained repeated pregnancy loss (the uRPL group) were almost twice as likely to be able to recognize their spouse’s odor as women who had not experienced the condition (the control group). Indeed, women in the control group performed no better than would be expected by chance (Figure 1A). Might this be due to women in the uRPL group simply having a better sense of smell? Rozenkrantz et al. found that women in the uRPL group were only marginally better at discerning odors in general, which suggests that the observed effect may be specific to smells that are socially important. Moreover, women in the uRPL group rated non-spousal odors differently from women in the control group in terms of perceived intensity, pleasantness, sexual attraction and fertility, again indicating that olfactory processing is altered in women who have experienced the condition.

Differences in how women who have experienced unexplained repeated pregnancy loss (uRPL) and women without the condition perceive odors, and how their brains process them.

(A) A group of women who have experienced uRPL and a control group were exposed to three different odors: a blank odor; the odor of their spouse; and a non-spouse odor. The number of women in the control group able to identify their partner’s odor could be explained by chance; the number of women in the uRPL group able to identify their partner’s odor was significantly higher. (B) Exposure to subliminal levels of male body odor while watching arousing movie clips elicits increased activity in the hypothalamus of women in the uRPL group (indicated in red; right), whereas hypothalamic activity decreases slightly in the control group (pale blue; left). Women in the uRPL group also had smaller olfactory bulbs. However, the precise links between altered olfactory processing in the brain and miscarriage are not yet fully understood.

Image credit: Joe Brock, Francis Crick Institute.

Rozenkrantz et al. next asked whether these differences in olfactory performance and perception were also reflected in brain form and function. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed that the olfactory bulb – the first brain structure that relays olfactory information from the nose – was significantly smaller in women in the uRPL group than in women in the control group (Figure 1B). This is a striking finding since smaller olfactory bulbs have previously been linked to poorer olfactory performance (Rombaux et al., 2010).

Rozenkrantz et al. next addressed whether the observed differences in the perception of male odors were reflected in altered brain activity. For this purpose, women from the uRPL and control groups were presented with non-spouse male odors while watching arousing movie clips in an MRI scanner. The initial analysis focused on the hypothalamus, a small but critical structure deep in the brain that links olfactory and reproductive functions. Rozenkrantz et al. found that activity in the hypothalamus increased in women from the uRPL group exposed to non-spouse male odor, while it decreased in women from the control group (Figure 1B). Additionally, exposure to non-spouse male odor increased correlated activity between the hypothalamus and the insula (an area in the cortex) significantly more in the control group than in the uRPL group. The link between these two brain areas may facilitate odor-based kin recognition (Lundström et al., 2009).

Overall, these experiments provide compelling evidence that women who have experienced unexplained repeated pregnancy loss perceive socially important odors in a different way, and that this is associated with specific changes in brain structure and function. However, this latest work does not reveal causal links between olfaction and the condition, and further research is needed to establish whether these differences in perception arise as a consequence of experiencing multiple miscarriages or whether they are present beforehand.

Rozenkrantz and colleagues – who are based at the Weizmann Institute of Science, the Edith Wolfson Medical Center and the Sheba Medical Center – also discuss conceptual similarities to the Bruce effect, a phenomenon first described in rodents, where pregnancy is terminated in females exposed to the scent of an unfamiliar male (Bruce, 1959). Since women in the uRPL group perceived non-spouse odors differently, this could be linked to an increased risk of miscarriage via a similar mechanism. However, the Bruce effect in rodents relies on brain structures that are nonexistent or vestigial in humans, casting doubts on the existence of this phenomenon in humans. Finally, it is also possible that partners of women experiencing unexplained repeated pregnancy loss might have a unique scent that contributes to repeated miscarriages. Exploring the possible mechanisms linking olfaction with unexplained pregnancy loss will thus be an important direction for future studies.

References

-

Molecular detection of pheromone signals in mammals: from genes to behaviourNature Reviews Neuroscience 4:551–562.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1140

-

The neuronal substrates of human olfactory based kin recognitionHuman Brain Mapping 30:2571–2580.https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20686

-

Male steroid hormones and female preference for male body odorEvolution and Human Behavior 27:259–269.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2005.11.002

-

Olfactory bulb volume and depth of olfactory sulcus in patients with idiopathic olfactory lossEuropean Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology 267:1551–1556.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-010-1230-2

-

Unexplained recurrent pregnancy lossObstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America 41:157–166.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2013.10.008

-

Modification of the oestrous cycle of the mouse by external stimuli associated with the maleJournal of Endocrinology 13:399–404.https://doi.org/10.1677/joe.0.0130399

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: September 29, 2020 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2020, Borak and Kohl

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 4,647

- views

-

- 106

- downloads

-

- 0

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Neuroscience

Nociceptive sensory neurons convey pain-related signals to the CNS using action potentials. Loss-of-function mutations in the voltage-gated sodium channel NaV1.7 cause insensitivity to pain (presumably by reducing nociceptor excitability) but clinical trials seeking to treat pain by inhibiting NaV1.7 pharmacologically have struggled. This may reflect the variable contribution of NaV1.7 to nociceptor excitability. Contrary to claims that NaV1.7 is necessary for nociceptors to initiate action potentials, we show that nociceptors can achieve similar excitability using different combinations of NaV1.3, NaV1.7, and NaV1.8. Selectively blocking one of those NaV subtypes reduces nociceptor excitability only if the other subtypes are weakly expressed. For example, excitability relies on NaV1.8 in acutely dissociated nociceptors but responsibility shifts to NaV1.7 and NaV1.3 by the fourth day in culture. A similar shift in NaV dependence occurs in vivo after inflammation, impacting ability of the NaV1.7-selective inhibitor PF-05089771 to reduce pain in behavioral tests. Flexible use of different NaV subtypes exemplifies degeneracy – achieving similar function using different components – and compromises reliable modulation of nociceptor excitability by subtype-selective inhibitors. Identifying the dominant NaV subtype to predict drug efficacy is not trivial. Degeneracy at the cellular level must be considered when choosing drug targets at the molecular level.

-

- Neuroscience

Despite substantial progress in mapping the trajectory of network plasticity resulting from focal ischemic stroke, the extent and nature of changes in neuronal excitability and activity within the peri-infarct cortex of mice remains poorly defined. Most of the available data have been acquired from anesthetized animals, acute tissue slices, or infer changes in excitability from immunoassays on extracted tissue, and thus may not reflect cortical activity dynamics in the intact cortex of an awake animal. Here, in vivo two-photon calcium imaging in awake, behaving mice was used to longitudinally track cortical activity, network functional connectivity, and neural assembly architecture for 2 months following photothrombotic stroke targeting the forelimb somatosensory cortex. Sensorimotor recovery was tracked over the weeks following stroke, allowing us to relate network changes to behavior. Our data revealed spatially restricted but long-lasting alterations in somatosensory neural network function and connectivity. Specifically, we demonstrate significant and long-lasting disruptions in neural assembly architecture concurrent with a deficit in functional connectivity between individual neurons. Reductions in neuronal spiking in peri-infarct cortex were transient but predictive of impairment in skilled locomotion measured in the tapered beam task. Notably, altered neural networks were highly localized, with assembly architecture and neural connectivity relatively unaltered a short distance from the peri-infarct cortex, even in regions within ‘remapped’ forelimb functional representations identified using mesoscale imaging with anaesthetized preparations 8 weeks after stroke. Thus, using longitudinal two-photon microscopy in awake animals, these data show a complex spatiotemporal relationship between peri-infarct neuronal network function and behavioral recovery. Moreover, the data highlight an apparent disconnect between dramatic functional remapping identified using strong sensory stimulation in anaesthetized mice compared to more subtle and spatially restricted changes in individual neuron and local network function in awake mice during stroke recovery.