Response to comment on ‘SARS-CoV-2 suppresses anticoagulant and fibrinolytic gene expression in the lung’

Abstract

Early in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, we compared transcriptome data from hospitalized COVID-19 patients and control patients without COVID-19. We found changes in procoagulant and fibrinolytic gene expression in the lungs of COVID-19 patients (Mast et al., 2021). These findings have been challenged based on issues with the samples (Fitzgerald and Jamieson, 2022). We have revisited our previous analyses in the light of this challenge and find that these new analyses support our original conclusions.

Introduction

As part of the global effort to address the pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, we support a robust discussion on COVID-19 to provide insight into the biological effect of the virus on humans. Previously, we compared transcriptome data from hospitalized COVID-19 patients to control patients without COVID-19 and found changes in procoagulant and fibrinolytic gene expression in the lungs of COVID-19 patients (Mast et al., 2021). These findings were subsequently challenged based on issues with the samples, including library depth, library preparation, and control group meta-data (FitzGerald and Jamieson, 2022). We have revisited our previous analyses of these two data sets, and we find that they are comparable to one another and support our conclusions. We address each of the criticisms of FitzGerald and Jamieson, 2022 below.

Results

The designation of Michalovich et al. as a “Healthy Control” for differential expression analysis

Fitzgerald and Jamieson have criticized our results based on the fact that the control group is (1) not free of comorbidities, and (2) "not representative of the American population". In accordance with eLife’s transparent reporting procedures, we list group allocation as “Cases were those individuals diagnosed with COVID-19, controls were from a separate study in which participants were not diagnosed with any viral infection”. Our goal of the analysis was to test for differences in the expression of genes in the coagulation pathway in response to infection from the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Most of the BALF samples in Michalovich et al. harbored comorbidities such as asthma, nicotine dependence, and obesity. Of the 40 control samples, three were reported to be free of these comorbidities (putatively 'healthy'). We find the criticisms raised are not warranted for the following reasons:

Fitzgerald and Jamieson make the assumption that the patients displaying COVID-19 from which the BALF samples were taken were healthy and had no comorbidities, however, comorbidities increase the risk of hospitalization with severe disease as well as mortality (King et al., 2020). We made no assumptions about the case samples and used what we believe to be a conservative approach by using all 40 control samples. Statistical significance may be more difficult to achieve with greater variance, therefore, only the strongest signals due to infection of the virus would be discovered.

Sub-group analysis can be informative but is vulnerable to Simpson’s paradox, ascertainment bias, and statistical power variability (unequal representation for each sub category). We did not perform a sub-group analysis as this was beyond the scope of the paper and not related to the hypothesis, which as we note above was differences in gene expression due to infection with a virus.

The samples of Michalovich et al. are from Poland and Switzerland, not the United States of America.

Dissimilar library preparation methods of Michalovich et al. (transcriptomic) and Zhou et al. (total RNA) are not comparable

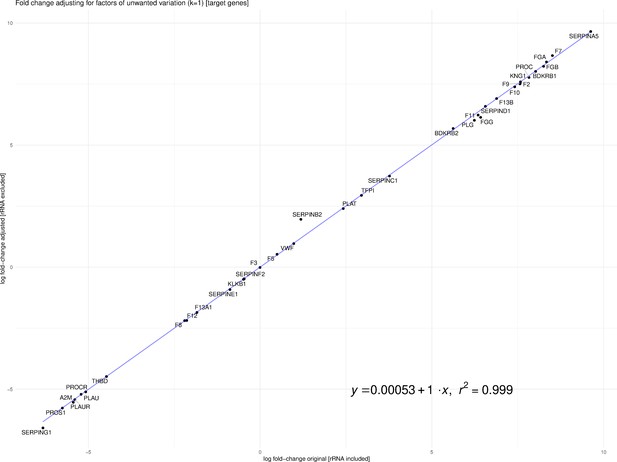

Fitzgerald and Jamieson state that dissimilar library preparation methods of Michalovich et al. (Transcriptomic) and Zhou et al. (Total RNA) are not comparable. Library preparation for the case and control samples was different for the two studies. Michalovich et al. used a polyA enrichment method, which removes most ribosomal RNA (rRNA), and for the 9 cases, total RNA that includes rRNA was prepared. However, the assumption that this makes the samples non-comparable is flawed. Previous work in the field of RNA-Seq analysis has developed tools and techniques to mitigate sources of technical variation, such as library preparation (Risso et al., 2014). Our analysis leveraged TMM normalized counts for the differential analysis, implemented in edgeR. Fitzgerald and Jamieson raise concerns about our differential analysis based on the findings of Zhao et al., 2020. However, Zhao et al. focused on TPM and did not discuss more robust normalization protocols such as TMM or RLE, and thus may not be applicable in this case. To address the concerns of Fitzgerald and Jamieson, we re-calculated log-fold change of the differentially expressed genes from our analysis after removing rRNA counts from the CLC Genomics output. Furthermore, we accounted for factors (k = 1) of putative technical variation using the RUVSeq R package thereby producing an adjusted log-fold change (Risso et al., 2014). As one can see in Figure 1, the log-fold change with rRNA and the adjusted log-fold change without rRNA are highly correlated (R2 ~0.99954).

Correlation between log-fold change with rRNA and the adjusted log-fold change without rRNA (R2 ~0.99954).

In addition, keeping all non-COVID-19 controls helps to resolve the issue where a gene is observed in COVID-19 samples but has few reads in the controls.

Insufficient read depth of samples from Zhou et al.

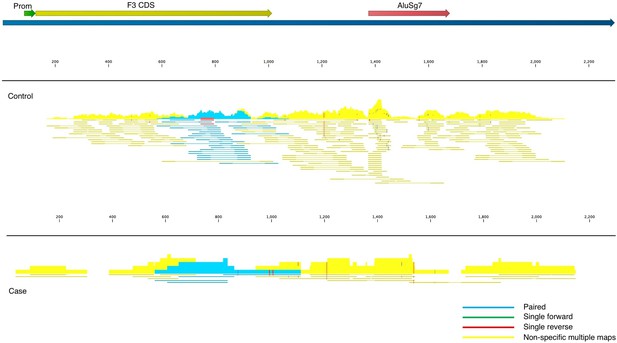

Fitzgerald and Jamieson state that COVID-19 BALF samples contain insufficient read depth. We acknowledge that there exist “generally accepted rules” for read depth, etc. in the field of transcriptome analysis, and these guidelines are important to adhere to wherever possible. The nine BALF samples used in our analysis were taken from severely ill patients in Wuhan China in an attempt to identify the as-yet-unidentified pathogen causing their symptoms and were not prepared in conjunction with control samples. The low read-depth of the nine BALF samples resulted in high false-positive (off-target) counts due to the presence of Alu elements in some of the transcripts, which can be seen in the read mapping files (Figure 2). To account for this, and to reduce inflation or deflation of expression levels, we used highly stringent mapping parameters in CLC Genomics Workbench. The default parameters for this algorithm are to score a “match” for a read if at least 0.80 of the fragment matches the gene and if the similarity is 0.8 or greater. Instead, to reduce off-target mapping, we used the much more conservative approach of 0.95 length and 0.95 similarity match.

Read mappings to the transcript NM_001993 for the F3 mRNA taken from one of the controls (top) and a case (bottom) used in Mast et al.

Mapping settings were set to mismatch cost = 2, insertion cost = 3, deletion cost = 3, length fraction = 0.95, similarity fraction = 0.95. The Alu element in the 3’UTR (brick), promoter (green), and coding sequence (dark yellow) of the transcript are annotated. Blue read mappings are paired reads that mapped a single time and light yellow are read mappings that aligned to multiple places in the transcriptome (i.e. other genes besides F3).

Given these highly stringent parameters, and the much larger read depth of the control samples, any genes that are expressed in COVID-19 BALF samples, but are not present in controls, have a high probability of being true positives and the fold-increase is likely an underestimate. We report large increases in many cases because the denominator of the controls was zero and therefore fold-change would be infinite. To account for this, we used the lowest number in the matrix of gene counts as the denominator.

Discussion

Fitzgerald and Jamieson state “By far the most notable result reported in Mast et al. is the reported observation that tissue factor, the key initiator of the extrinsic coagulation cascade, is not significantly impacted by SARS-CoV-2 infection”. As noted previously, the presence of Alu elements can provide spurious read mappings in the situation where there are low read counts, as is the case here. Indeed, not only does tissue factor (F3) contain an Alu element in the 3’UTR of the gene, the read mapping file in CLC Genomics Workbench clearly shows for both cases and controls, that the majority of the fragments map to multiple places in the transcriptome (yellow in Figure 2), and cannot be assigned to F3 with confidence. Regardless, in these BALF samples, F3 does not appear to be expressed at the mRNA level in cases or controls to any appreciable level. F3 may be upregulated in other tissues or cell types, or it may also be regulated at the protein and/or activity level, i.e., our analysis does not preclude a role of F3 in the complex pathology of COVID-19. For example, increased tissue factor has been detected by flow cytometry in monocytes and platelet-monocyte aggregates (Hottz et al., 2020) and by confocal microscopy and RT-qPCR in neutrophils (Skendros et al., 2020) from critically ill COVID-19 patients. Interestingly, it has been reported that a SARS-CoV-2 spike protein pseudovirus increases tissue factor activity in cells by converting it from an inactive to active form without altering protein expression (“decryption”) (Wang et al., 2021), which is consistent with our results.

In their Discussion the authors state that “the field has begun converging on tissue factor as a key player in the pathogenesis and coagulopathy complications of SARS-CoV-2 infection”. As stated above, we applaud the scientific community for their continued focus on this pathway and we are proud to have contributed to it early in the pandemic. We trust that the community does not think that we claim to have provided a complete and final understanding of COVID-19’s effects in the lungs. Solutions to complex problems are achieved from a consensus of researchers addressing them with multiple approaches, one of which is our study.

Data availability

Previously published data sets with BioProject IDs PRJNA605983 and PRJNA434133 were used.

-

NCBI BioProjectID PRJNA605983. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 Raw sequence reads.

-

NCBI BioProjectID PRJNA434133. Microbiome and Inflammatory Interactions in Obese and Severe Asthmatic Adults.

References

-

Normalization of RNA-seq data using factor analysis of control genes or samplesNature Biotechnology 32:896–902.https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2931

-

Complement and tissue factor-enriched neutrophil extracellular traps are key drivers in COVID-19 immunothrombosisThe Journal of Clinical Investigation 130:6151–6157.https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI141374

Article and author information

Author details

Funding

No external funding was received for this work.

Senior Editor

- Jos W Van der Meer, Radboud University Medical Centre, Netherlands

Reviewing Editor

- Noriaki Emoto, Kobe Pharmaceutical University, Japan

Version history

- Received: October 25, 2021

- Accepted: November 24, 2021

- Version of Record published: January 11, 2022 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2022, Mast et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 357

- views

-

- 33

- downloads

-

- 1

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Computational and Systems Biology

Transcriptomic profiling became a standard approach to quantify a cell state, which led to accumulation of huge amount of public gene expression datasets. However, both reuse of these datasets or analysis of newly generated ones requires significant technical expertise. Here we present Phantasus - a user-friendly web-application for interactive gene expression analysis which provides a streamlined access to more than 96000 public gene expression datasets, as well as allows analysis of user-uploaded datasets. Phantasus integrates an intuitive and highly interactive JavaScript-based heatmap interface with an ability to run sophisticated R-based analysis methods. Overall Phantasus allows users to go all the way from loading, normalizing and filtering data to doing differential gene expression and downstream analysis. Phantasus can be accessed on-line at https://alserglab.wustl.edu/phantasus or can be installed locally from Bioconductor (https://bioconductor.org/packages/phantasus). Phantasus source code is available at https://github.com/ctlab/phantasus under MIT license.

-

- Computational and Systems Biology

- Evolutionary Biology

A comprehensive census of McrBC systems, among the most common forms of prokaryotic Type IV restriction systems, followed by phylogenetic analysis, reveals their enormous abundance in diverse prokaryotes and a plethora of genomic associations. We focus on a previously uncharacterized branch, which we denote coiled-coil nuclease tandems (CoCoNuTs) for their salient features: the presence of extensive coiled-coil structures and tandem nucleases. The CoCoNuTs alone show extraordinary variety, with three distinct types and multiple subtypes. All CoCoNuTs contain domains predicted to interact with translation system components, such as OB-folds resembling the SmpB protein that binds bacterial transfer-messenger RNA (tmRNA), YTH-like domains that might recognize methylated tmRNA, tRNA, or rRNA, and RNA-binding Hsp70 chaperone homologs, along with RNases, such as HEPN domains, all suggesting that the CoCoNuTs target RNA. Many CoCoNuTs might additionally target DNA, via McrC nuclease homologs. Additional restriction systems, such as Type I RM, BREX, and Druantia Type III, are frequently encoded in the same predicted superoperons. In many of these superoperons, CoCoNuTs are likely regulated by cyclic nucleotides, possibly, RNA fragments with cyclic termini, that bind associated CARF (CRISPR-Associated Rossmann Fold) domains. We hypothesize that the CoCoNuTs, together with the ancillary restriction factors, employ an echeloned defense strategy analogous to that of Type III CRISPR-Cas systems, in which an immune response eliminating virus DNA and/or RNA is launched first, but then, if it fails, an abortive infection response leading to PCD/dormancy via host RNA cleavage takes over.